Under the Red Ensign

Oil on canvas, late eighteenth century, ca. 1780–1800

Collection of Private Manoeuvres

Officers and Lovers

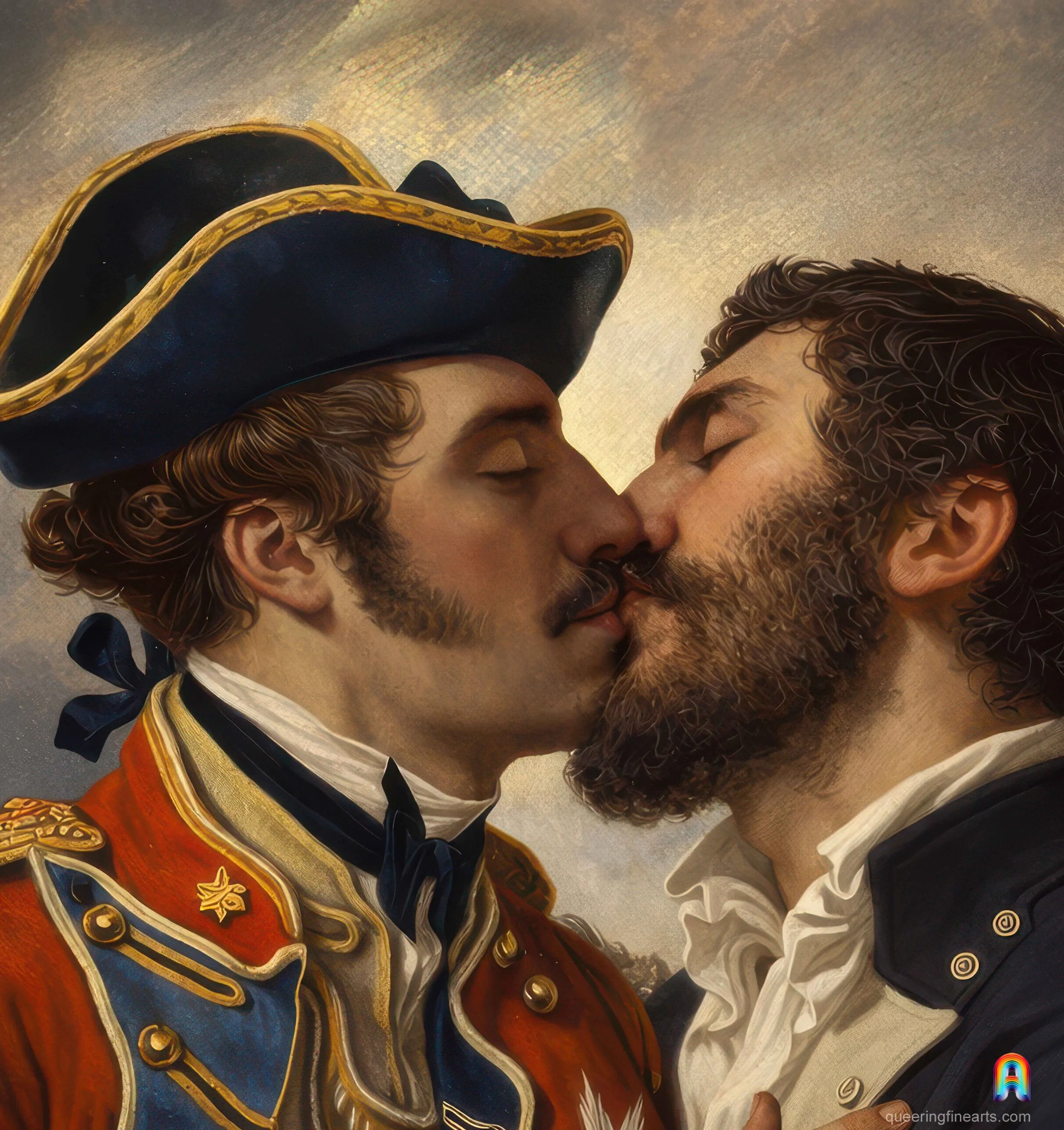

At first glance, the work presents itself as an eighteenth-century military genre scene, depicting men in uniform gathered in an ordinary space of sociability, around tables, conversations, and a glass placed in the foreground¹. The composition initially appears familiar, almost conventional, inscribed within a pictorial register well established in British painting of the period².

A Genre Scene in Trompe-l’Œil

At the center of the composition, two British officers, John Money and Charles White, are shown sharing a calm and self-assured kiss³. Their bodies touch with restraint, Money’s hand resting on White’s chest, while their closely drawn faces establish a silent intimacy. The uniforms clearly situate the figures within an eighteenth-century military milieu. Around them, a group of men gathered at tables converse. Some glances turn toward the central couple, while others remain absorbed in their exchanges, creating an atmosphere of intimate and joyful sociability⁴.

Virile Solidarities

The scene unfolds in front of a molly house, identifiable as a male meeting place⁵, though presented here without reference to its clandestine character at the time. In this sense, the work firmly belongs to the tradition of military genre painting, while profoundly shifting its boundaries, as male intimacy is shown with a freedom and visibility exceptionally rare in this type of representation⁶.

A Solid Military Career

John Money (1752–1817) was a British officer whose career, without reaching the highest levels of command, nevertheless reflects a solid, varied, and respected trajectory. He entered the army in 1770 as an ensign and served in North America during the American Revolutionary War, where he was wounded at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775⁷. He subsequently took part in campaigns conducted from Canada, notably that of General Burgoyne, and was present at the British defeat at Saratoga in 1777⁸. Thereafter, Money distinguished himself through particular skills in reconnaissance and cartography, leading him to undertake sensitive intelligence missions⁹, notably in the Netherlands in the early 1780s.

From the Front to the Staff

In the 1790s, he served in Europe during the wars against Revolutionary France and distinguished himself during the British army’s retreat in Flanders in 1794, where he commanded a rearguard with composure and effectiveness. He concluded his career in engineering and military administrative roles, notably within the Royal Staff Corps¹⁰, before retiring with the rank of lieutenant general. His career exemplifies the profile of a competent, courageous, and versatile officer whose reputation rested more on service rendered than on public glory.

Homosexual!

The major historical interest of John Money lies in the fact that his homosexuality is attested on exceptionally solid archival grounds for a British officer of the eighteenth century¹¹. Unlike other contemporary figures whose sexual orientation rests on rumor, satirical songs, or political insinuation, Money’s case is documented through direct private sources and through his insertion within an identifiable social network. He maintained an ongoing romantic relationship with a young officer, Charles White, a relationship known to historians through explicit personal correspondence preserved in the archives, even though it has never been published in full¹².

A Discreet Network

Moreover, Money is identified as a member of a network linked to London’s molly houses, spaces of male homosexual sociability well documented by judicial and police archives of the period¹³. This affiliation situates him not in isolation or mere individual transgression, but within a structured urban subculture, with its own places, codes, and informal protections. Finally, the fact that he was never prosecuted, despite the extreme criminalization of sodomy¹⁴, can be explained by the combination of his rank, his social connections, and the discreet and consensual nature of his relationships.

An Exceptional Testimony

For historians of sexuality and of the military world, John Money thus constitutes a rare and precious case, demonstrating that under certain conditions, men occupying elevated positions could live a real and acknowledged homosexuality, leaving written traces sufficiently clear to move beyond rumor and enter fully into documented history¹⁵.

Charles White: The Lover

Charles White was a junior officer in the British army active during the 1770s and 1780s, known today almost exclusively through the traces he left in John Money’s private correspondence and through archival cross-referencing that allows his career to be situated. He belonged to a generation of young officers drawn from the lower gentry or upper middle classes, for whom the army represented both a means of social advancement and a framework of intense male sociability. White served alongside Money during the campaigns of the American Revolutionary War, and later in various military contexts where daily proximity, shared dangers, and garrison life fostered close personal bonds.

A Partner in Military Life

Without attaining high rank or public notoriety, he appears as a competent officer sufficiently appreciated to remain durably within Money’s circle. His historical importance lies less in an exceptional career than in the central place he occupies within a documented romantic relationship, a rare testimony to the lived experience of a homosexual man within the eighteenth-century British army—not as a scandalous figure or a judicial victim, but as an affective partner embedded in the ordinary reality of military service¹⁶.

The Language of Intimacy

In the intimate correspondence addressed to Charles White, John Money employs an affectionate and loving language of exceptional clarity for his time. He writes explicitly, “I languish for you… I think incessantly of your bodily presence, and desire nothing more than to clasp you in my arms,” expressing a longing both physical and emotional that clearly exceeds ordinary military camaraderie. Elsewhere, he evokes with equal frankness the carnal memory of his lover, speaking of “the softness of your body, the warmth of your contact,” and expressing a renewed desire to recover that intimacy. He also affirms the priority and exclusivity of this attachment, declaring that no other company provides him with “contentment comparable,” emphasizing that the moments shared with White are those in which he feels “most fully myself.” Finally, a note of amorous anxiety runs through certain letters, when Money confides his fear of losing White, not only as a companion in arms but as the “object of my love,” the idea of injury or death provoking in him a “profound personal anguish.” Taken together, these quotations attest to an openly articulated love, assumed in both its affective and corporeal dimensions, and exceptionally legible within the archives of the eighteenth century¹⁷.

(For further context on the dating and duration of this correspondence, see the section Timeframe of a Love in Letters at the end of the text.)

Molly House: Origin of the Term

The expression molly house appears in England in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, primarily in London. The word molly was then a pejorative nickname applied to men perceived as effeminate or as transgressing gender norms. It most likely derives from the feminine diminutive of Mary, used mockingly, although some historians have also suggested a possible link with the Latin mollis. The term was not claimed by the men who frequented these places, but was forged by authorities, moralists, and judicial chroniclers. House simply refers to the physical space—tavern, back room, coffeehouse, or private lodging. The designation is thus stigmatising from the outset and reflects the hostile gaze cast upon these forms of male sociability.

Spaces of Male Sociability

Molly houses were not brothels in the strict sense, but polyvalent social spaces. One drank, danced, flirted, exchanged information, and arranged sexual encounters. Some sources also mention collective rituals such as symbolic marriages, parodic baptisms, or gendered role-playing, which testify to a shared and codified culture¹⁹. These places were frequented by men of diverse social origins—artisans, servants, apprentices, soldiers, sailors—and sometimes by individuals of higher rank who attended with caution. Their existence is known almost exclusively through sources of repression—sodomy trials, police reports, and moralizing pamphlets—which explains the often distorted and hostile vision that has come down to us.

A Pivotal Moment for Queer Life

Molly houses constitute a fundamental moment in the history of queer life, for they show that relationships between men were not limited to furtive or isolated encounters. They reveal the existence of organized collective spaces in which desire, identity, and sociability could be articulated in a durable way, well before the emergence of modern sexual categories. Despite the extreme risks involved—sodomy being a capital crime—these places testify to a remarkable capacity to create networks, forms of mutual recognition, and a shared culture. As such, molly houses can be regarded as one of the first documented centers of an urban homosexual subculture in Europe, and as an essential milestone for understanding the long history of queer visibility, solidarity, and resistance²⁰.

A Fortunate Exception

In this context, John Money appears as a particularly luminous figure. His life shows that in the eighteenth century, despite legal repression, spaces of possibility existed for a real, affective, and lasting homosexuality. A respected, integrated, and loved officer, Money embodies a positive and lived experience of love between men, embedded in the everyday life of military service. The traces he left do not tell a story of fear or scandal, but rather of the rare and precious possibility of living and loving fully—and of leaving that imprint in history²¹.

Timeframe of Their Love Letters

Bathed in warmth, longing, and an unmistakable tenderness, these letters carry the pulse of a love that was both deeply felt and carefully preserved in words. One can situate them within a reasonably precise chronological range, even though no complete and fully dated edition survives.

Historians generally agree that the core of this intimate correspondence belongs to the period between the mid 1770s and the early 1780s, during and immediately following the American War of Independence. This dating rests on several solid converging elements. The relationship between Money and White is attested at a time when White was still serving as a junior officer on active duty, which corresponds to this phase of their lives. The tone of the letters repeatedly evokes separation, danger, and uncertainty, experiences closely tied to North American military campaigns and to the constant movements imposed by service, before Money moved into more specialized roles in intelligence and staff duties later in the 1780s. Finally, scholars such as A D Harvey and Emma V Macleod place these exchanges in what appears to be the most intense period of Money’s emotional life, before his career settled and the correspondence became more sporadic.

It is therefore historically sound to date these letters to around 1775 to 1782, without claiming precision to a particular month or year. This period most likely captures only a central phase of their bond, which appears to have begun well before and to have endured long after the surviving correspondence. Within and beyond this span of time unfolds a love whose emotional heat and mutual devotion give enduring form to an attachment remarkable for its clarity, its courage, and its quiet beauty.

Curiosity Piqued?

Solkin, David H., Painting for Money: The Visual Arts and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century England, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993.

Retford, Kate, The Conversation Piece: Making Modern Art in Eighteenth-Century Britain, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2016.

Norton, Rictor, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, New York, Garland, 1984.

Retford, Kate, The Conversation Piece, op. cit.

Norton, Rictor, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700–1830, London, GMP, 1992.

Pointon, Marcia, Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993.

Mackesy, Piers, The War for America, 1775–1783, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Mackesy, Piers, The War for America, op. cit.

Mackesy, Piers, ibid.

Cookson, J. E., The British Armed Nation, 1793–1815, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1997.

Norton, Rictor, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, op. cit.

Norton, Rictor, Mother Clap’s Molly House, op. cit.

Trumbach, Randolph, Sex and the Gender Revolution, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Bray, Alan, Homosexuality in Renaissance England, London, Gay Men’s Press, 1982.

Trumbach, Randolph, Sex and the Gender Revolution, op. cit.

Trumbach, Randolph, ibid.

Norton, Rictor, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England, op. cit.

Norton, Rictor, Mother Clap’s Molly House, op. cit.

Trumbach, Randolph, “London’s Sodomites,” Journal of Social History, 1991.

Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, New York, Pantheon Books, 1978.

Cook, Matt, London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885–1914, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.