Rainbow Stained Glass

Harmodios and Aristogeiton

Stained glass, circa 1340

Unknown collection

Male Love and the Birth of Political Freedom

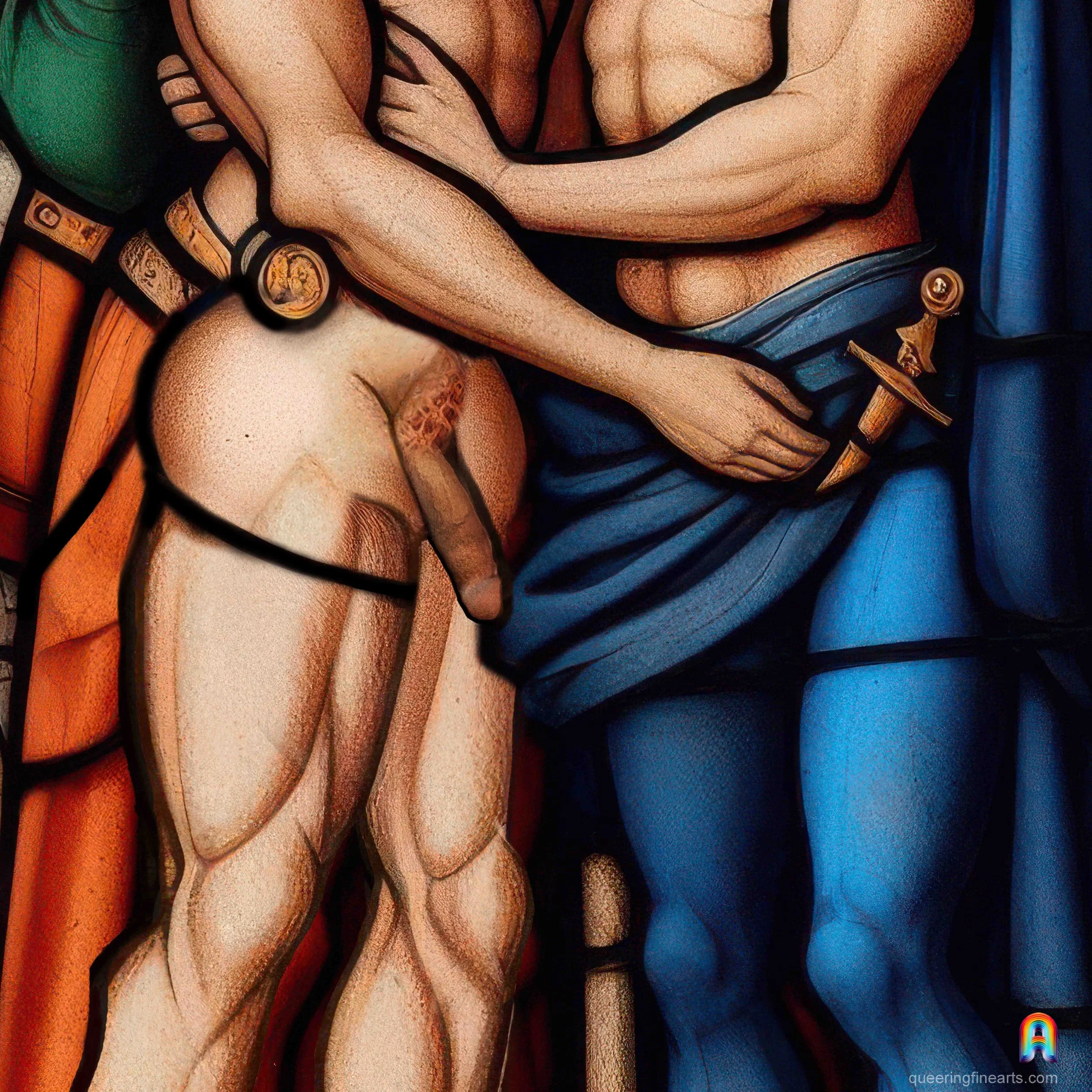

The stained glass, of striking chromatic intensity, unfolds in a vertical composition structured by Gothic arcades. At its center emerges the principal group formed by two men, identified as Harmodios and Aristogeiton, shown in explicit physical intimacy¹. The two figures are entwined and kiss on the mouth. One of the lovers is nude, his nakedness rendered with notable anatomical precision. The other wears a short draped garment, yet his body is equally emphasized. His hand rests on his companion’s body, and he carries a short dagger, set in direct contrast with the act of tenderness².

Virile Solidarities

Surrounding this central couple, other male figures occupy the adjacent lancets. They are possibly Athenian citizens or warriors. One bears a sword, another a kind of staff, phallic symbols underscoring the masculine world in which the narrative unfolds³. These figures also appear in pairs, marked by close physical proximity. Their faces are treated with softness, eyes closed or half closed, expressions calm and almost contemplative⁴.

Convergence

The upper section is filled with a rich ornamental program composed of stylized vegetal motifs, foliage, and interlace, rendered in deep blues and greens, forming an autonomous register distinct from the human narrative⁵. Taken as a whole, the stained glass tightly weaves together nudity, weapons, and embraces. Athenian resistance to tyranny is not conveyed through a scene of combat, but through a network of solidarized male bodies, with the central couple serving as the visual and symbolic point of convergence⁶.

A Context, a Couple

In Athens, at the end of the sixth century BCE, the city was ruled by the Peisistratids, a dynasty founded by the statesman Peisistratos. After his death, his sons Hippias and Hipparchos held power, concentrating authority in the hands of a few⁷. It is within this context that Harmodios and Aristogeiton emerge, two citizens bound by a male love relationship recognized within the social codes of the time⁸. Their bond, both intimate and public, would soon be placed at the heart of a major political narrative.

From Intimate Conflict to Political Act

In 514 BCE, during the Panathenaia, the great civic and religious festival, Harmodios and Aristogeiton attempted to strike down the two brothers⁹. Their primary target was Hippias, the ruling tyrant, but the plot partially failed and it was Hipparchos who was killed. Harmodios was slain immediately, while Aristogeiton was arrested, tortured, and executed shortly thereafter. Tradition reports that the immediate trigger was an offense that directly affected their relationship. Hipparchos is said to have sought to seduce Harmodios and, after being rebuffed, publicly humiliated his sister during a procession. The injury to the couple’s honor, to eros and to the implicit rules governing relations between citizens, thus transformed into a rejection of tyranny¹⁰.

Civic Recognition of a Male Couple

The tyranny did not fall immediately. Hippias remained in power until 510 BCE, when he was overthrown. Yet from the establishment of democracy onward, Athens elevated Harmodios and Aristogeiton as founding heroes. Their memory was honored with a bronze statue erected in the Agora, with civic privileges granted to their descendants, and with banquet songs, the skolia, which celebrated their deed as the symbolic origin of equality before the law¹¹. This glorification did not retain only the political act; it also magnified the masculine union itself. Love between men appears here as a formative force of virtue, a source of courage, loyalty, and sacrifice, and as one of the sites where Athens bound eros and aretē, desire and moral excellence, in the service of freedom.

Middle Ages and Antiquity

Harmodios and Aristogeiton appear in this Gothic stained glass as transitional figures. They embody the Middle Ages’ capacity to absorb Antiquity and to transform it into a reservoir of moral exempla¹². Their presence suggests that such a stained glass window could have existed, even if its actual realization would have been rendered problematic by the dominant values of the period.

Moral Limits of the Middle Ages

For the Middle Ages cannot, in themselves, be taken as a model of exemplary morality. Politically, tyranny was often conceived as a legitimate form of power, willed or permitted by God, and the very idea of political resistance remained largely suspect. Likewise, homosexuality, though omnipresent in social practices and in courtly or clerical cultures, was officially condemned, concealed, reinterpreted, or denied¹³. That a loving male couple, even sublimated into amicitia, a virile and spiritual friendship, could be integrated into a sacred iconographic program therefore belongs to the realm of conjecture.

The Truly Timeless Values

It is precisely this tension that makes such a stained glass intellectually and symbolically powerful. By contrast, it reveals that medieval hostility toward homosexuality was neither universal nor timeless, but historically situated, just like the relative acceptance of tyranny¹⁴. By invoking Harmodios and Aristogeiton, the image recalls that love between men has, at times, been publicly praised as a source of civic virtue, courage, and freedom¹⁵, and that certain ancient values, the union of bodies, masculine solidarity, the refusal of oppression, may appear, in retrospect, more emancipatory than those of later eras¹⁶.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, VI, 54 to 59.

2. Nicole Loraux, The Divided City. Paris, Payot, 1997.

3. David M. Halperin, One Hundred Years of Homosexuality. New York, Routledge, 1990.

4. Kenneth J. Dover, Greek Homosexuality. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1978

5. Jean Claude Bonne, L’Ornement. Paris, Gallimard, 1993.

6. Nicole Loraux, The Invention of Athens. Paris, La Découverte, 1981.

7. Herodotus, Histories, I.

8. Eva Cantarella, Bisexuality in the Ancient World. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1992.

9. Aristotle, The Constitution of Athens, 18 to 19.

10. Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, VI, 56 to 57.

11. Pausanias, Description of Greece, I, 8.5 to 8.6.

12. Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods. Paris, Flammarion, 1980.

13. Mark D. Jordan, The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1997.

14. R. I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society. Oxford, Blackwell, 1987.

15. Thomas K. Hubbard, A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Malden, Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

16. Martha C. Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986.