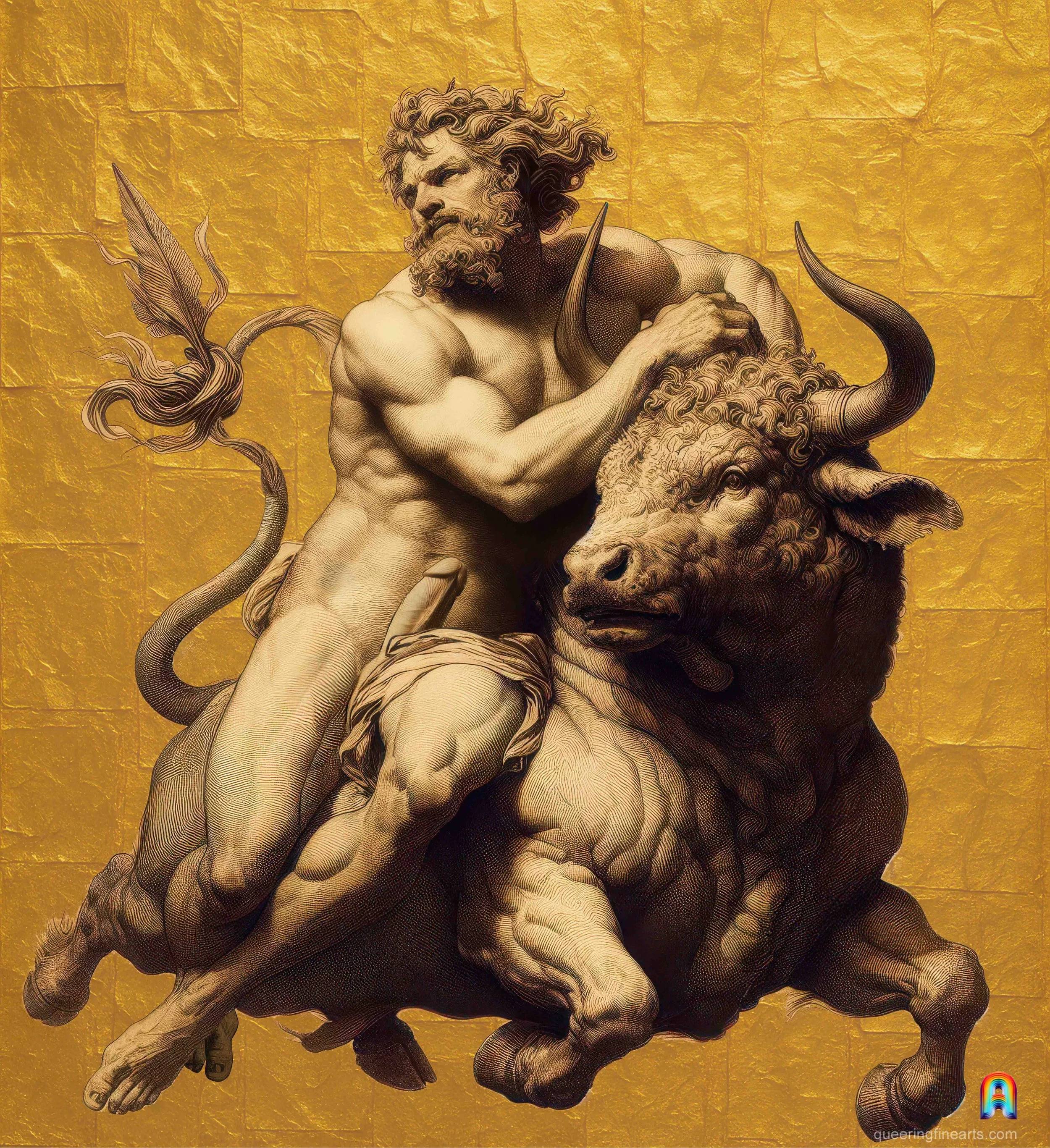

The Abduction of Cadmus

In the manner of Jacques-Louis David

Burin engraving on gold-leaf ground, c. 1770

Private collection

Against the Grain of the Rape of Europa

Cadmus, hero of Greek mythology and future founder of Thebes, is first known for having been sent to search for his sister Europa, abducted by Zeus in the form of a bull. The image here proposes an intentional inversion of that tradition. The ancient tale is rooted in an act of abduction framed as a charming scene: Europa deceived by a gentle animal, carried far from her homeland, stripped of her voice and of any power over her destiny. The structural violence of the episode is erased by poetic aesthetics, while the cunning and desire of Zeus are celebrated. Europa becomes a narrative pivot without subjectivity, instrumentalized to produce lineages and kingdoms for the benefit of masculine power¹.

Shaking the Myth

It is precisely by taking this profoundly problematic dimension into account that this reinvention chooses another path, not without a subtle wink. Instead of an abduction disguised as romance, the scene shows a willing Cadmus, fully consenting, responding to the power of the divine bull rather than suffering it. Where tradition imposes coercion, this version introduces free will; where the aggressor was glorified, the “abducted” figure is given back his desire and agency. No more silence, no more ruse, no more hidden violence: a myth overturned, freed from the patriarchal structures that shaped it, and reread with a knowing glance².

Musky Voluptuousness

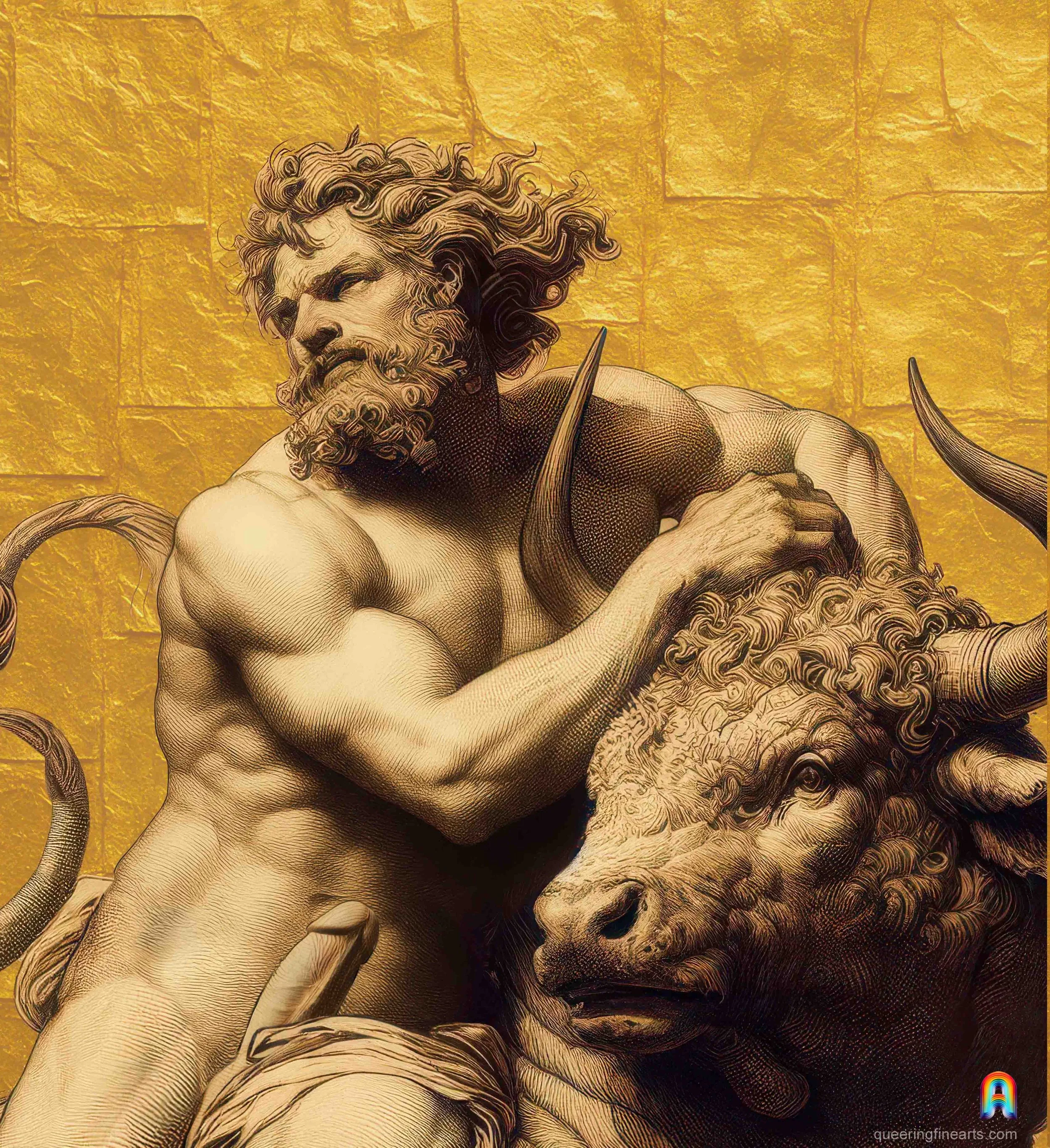

Cadmus saw before him the sudden apparition of a bull whose power seemed to vibrate in the very air. He understood Zeus’s intention and chose to subvert it, whatever the cost. The son of Agenor, Phoenician king of Tyre or Sidon depending on the version, froze for an instant at the sight of the animal’s muscular mass, the tension of the neck, the dark gleam in the eyes where the consciousness of a god flickered. Tradition says that Zeus hesitated briefly, but charmed by the prince — and himself intoxicated by his own exhalation of musky fertile heat — he stepped forward slowly, ready to seduce, deceive, capture. Cadmus, however, grasped the intention immediately and short-circuited it by stepping forward deliberately, almost offering himself. He placed his hand on the warm crest of the bull’s neck and, in that gesture, overturned the entire logic of the myth⁴.

The Awakening of Two Beasts

He was no longer a trapped victim but a man accepting the encounter. The seminal force of the bull, ancient symbol of fertility and rutting strength, struck through him like a jolt. The contact became an invitation to which his body responded without hesitation, in a rush of desire so unmistakable that his erection seemed itself worthy of the superlatives of an ancient myth. Zeus, caught off guard, had to revise his role. Cunning became useless, domination meaningless. The god understood he had nothing to seize from a mortal who came freely to him, and he accepted it, almost calmed by this inversion in which, for once, consent opened the way to legend⁵.

Sacred Rut

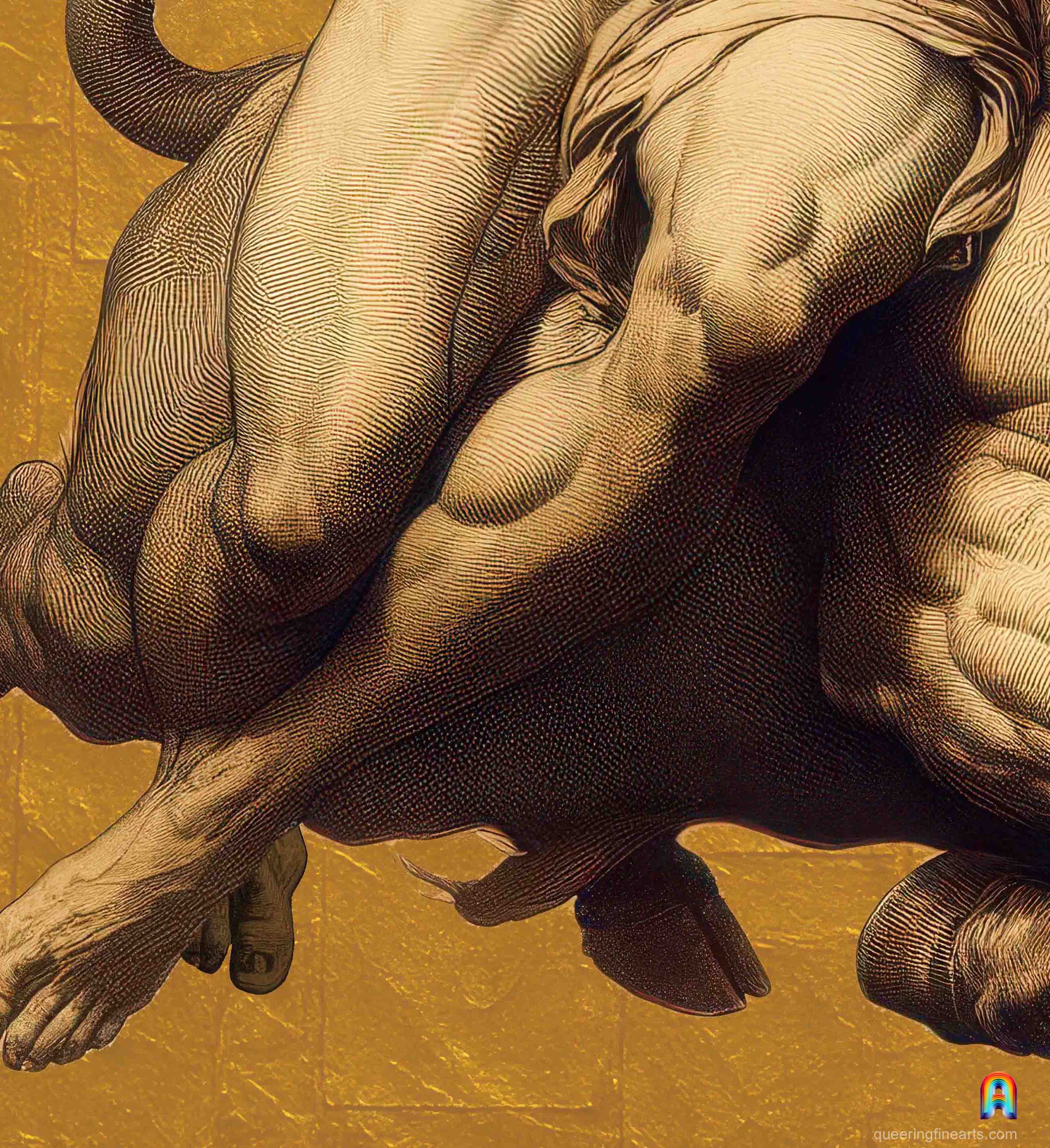

The scene presents a vigorous, near-nude Cadmus whose heroic anatomy is rendered through tight hatching typical of eighteenth-century French engraving. Parallel strokes and cross-shading sculpt the forms with a precision reminiscent of academic practice, where artists sought to give the male figure the monumentality of marble. The bull, in turn, is treated with striking graphic energy: the striations of its hide, the tension of the neck, the shadows sliding beneath the muscular mass indicate a sacred creature rather than a domestic animal. The gold background, seemingly applied afterward, acts as a liturgical screen that heightens the ceremonial aura of the print. The carnal proximity between man and bull — taut bodies, shared momentum, fused impulse — clearly overturns the myth of the Abduction of Europa into an episode where desire, animal force, and freedom of gesture merge in a sensual epiphany.

The Neoclassical Nose Peeks Through

The most plausible attribution would situate this engraving within French production of the mid-eighteenth century, at a time when workshops were exploring combinations of expressive intaglio and pre-neoclassical vocabulary. The rigorous anatomical treatment recalls plates produced in the circle of the young Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) in Rome, where artists already sought to unite academic precision with dramatic tension. The vigorous modeling of the bull evokes those artists influenced by Edme Bouchardon (1698–1742), whose taste for monumental beasts appears in several engravings of the period.

Fertile Prince

The union between Cadmus and Zeus transformed into a bull, as imagined here, fits into a surprisingly fertile genealogy. Although the ancient myth does not explicitly recount their carnal encounter, it does affirm that Cadmus becomes one of the great founders of divine lineages: husband of Harmonia, daughter of Ares and Aphrodite⁶, he fathers Semele, mother of Dionysus⁷, along with Ino, Agave, Autonoe, and Polydorus⁶. Through them arise entire branches of Greek mythology, from the Theban house to the Dionysian dramas⁸. In this reinvention, the shared momentum between the god and the Phoenician prince becomes a symbolic spark that quietly prepares the birth of an entire strand of the Greek world.

Europa Reimagined

Europa, for her part, regains in this renewed reading a role all the stronger for being freed from the violence and subjection of the ancient traditions. Released from the coercion structuring her tale, she becomes once again an active figure, a founding presence whose place in the Cadmean genealogy no longer depends on abduction or domination⁹. Thus Cadmus and Europa form the two poles of the same mythological renewal: one through his fertile union with the divine, the other through the reclamation of her own story, finally freed from the silence imposed by patriarchal tradition¹⁰.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. Keck, David. Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press, 1998.

2. Daniélou, Jean. Les Anges et leur mission. Éditions du Cerf, 1952.

3. von Stuckrad, Kocku. Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury, 2014.

4. Keck, David. Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

5. Halberstam, Jack. Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters.

6. Apollodorus, Library, III.4.2.

7. Hesiod, Theogony, lines 937–943.

8. Pausanias, Description of Greece, IX.5.1–3.

9. Ovid, Metamorphoses, II.833–875; Moschus, Europa, 1–20.

10. Loraux, Nicole. Les Enfants d’Athéna. Maspero, 1981; Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves. Schocken Books, 1975.