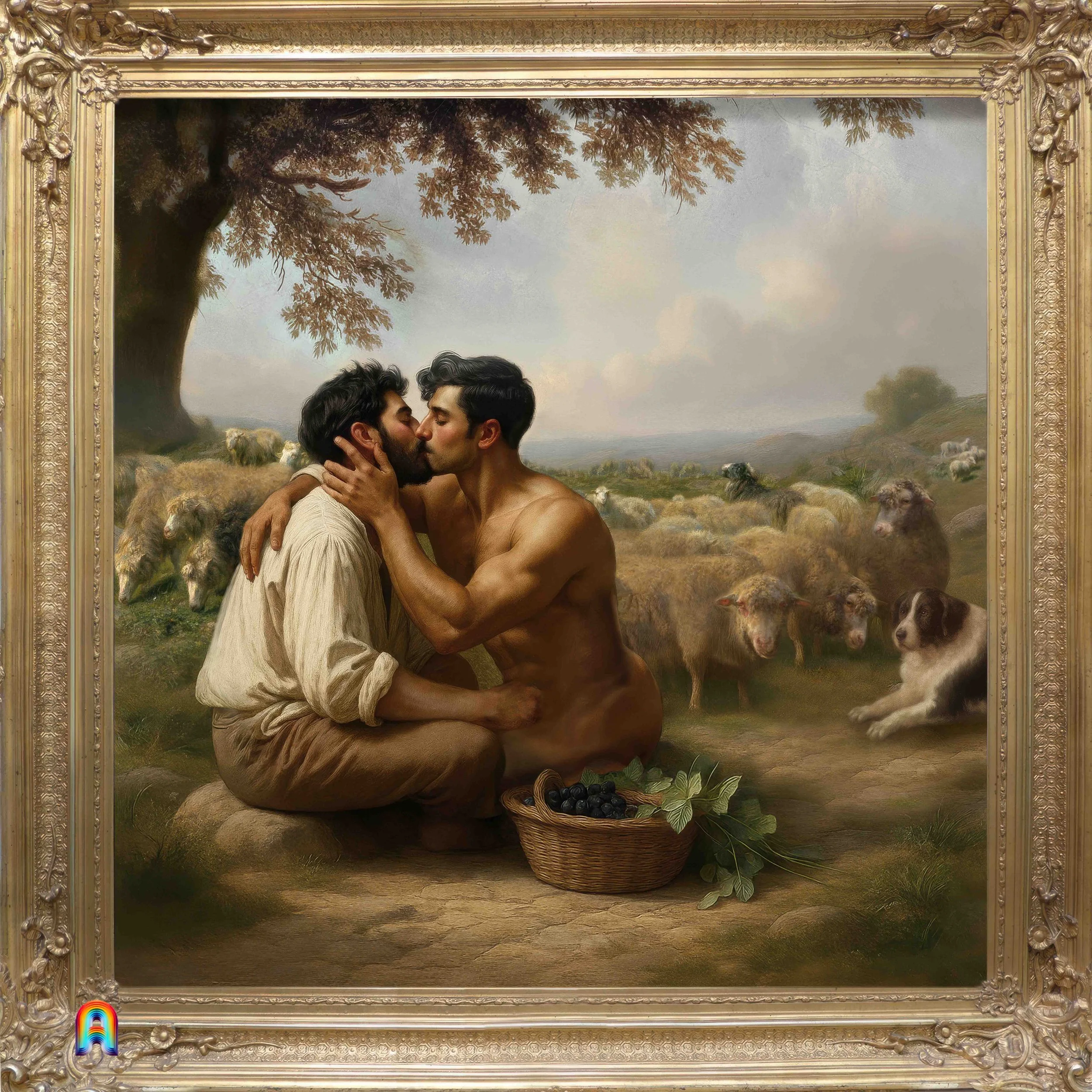

L’Ideale

Italian school, probably Roman or Neapolitan

Oil on canvas , late nineteenth century

Collection of Castello Pecora Nera

Arcadian Revival

The composition unfolds like an homage to the Italian pastoral tradition, where shepherds, flocks, orchards and broad skies formed a poetic vocabulary for longing. Two young men meet in a clearing, their bodies relaxed and bathed in warm Mediterranean light. The atmosphere recalls the sentimental naturalism prized in nineteenth-century Rome, an art that sought not only to record rural life but to elevate it into a vision of harmony.

And in a playful touch, the lone black sheep becomes a stand-in for the artist himself, whose work reminds us of what Arcadia should always have been, a place that fully includes gay lives. In this context, the idealization supports a scene of tenderness long excluded from academic pastoral painting, allowing tenderness between men to take its place within a pastoral tradition long molded by norms that pushed non-normative desire out of sight¹.

Subversive Naturalism

Building on this, the canvas resonates with the legacy of Filippo Palizzi (1818–1899) and the animal-painting circles of Naples and Rome. However, the artist engages in a act of subversive naturalism. He adopts the technical codes of this tradition—anatomical accuracy, the luminous rendering of a specific place, the emblematic herds—but redirects their purpose. The hyper-realistic wool of the sheep and the meticulous botany are not just a tribute to truth in art; they become the very tools to legitimize a scene that the 19th-century worldview would have deemed "against nature." This precise, almost scientific realism is weaponized to anchor queer intimacy firmly within the natural order, making it irrefutable and serene².

Gentlemen of the Meadow

This painting draws from a very specific tradition: the Ancient pastoral. For the Greek poet Theocritus (3rd century BC) and the Roman Virgil, Arcadia was already a land of shepherds who were musicians and lovers. But there is a crucial detail: in these foundational texts, relationships between men were a normal and celebrated component of the idyllic life. Male homosexuality was not "off-screen"; it belonged to the scene. It was part of the myth.

The great feat of this painter is therefore this: he is not "reinventing" Arcadia. He is restoring its historical truth. His bold stroke was to transpose this authentic, classical vision into the world of 19th-century academic art, a context where such a direct depiction would have been nearly unthinkable. He performs a double act of revival: reaching back beyond the sanitized Renaissance and Baroque traditions to reclaim Arcadia's original spirit, and daring to place it squarely before a modern audience.

While 19th-century academic painting across Europe had refined and hetero-centered this tradition, this work is a corrective return to the sources. It does not corrupt the pastoral genre; it purges it of the moralizing censorship of its time. The kiss between the two shepherds is not a modernist provocation, but a restoration: it is the return of a long-repressed, foundational theme to the representation of the golden age.

In short, the painter reminds us of a forgotten obvious truth: the first lost paradise of Western art was also, originally, a queer paradise³.

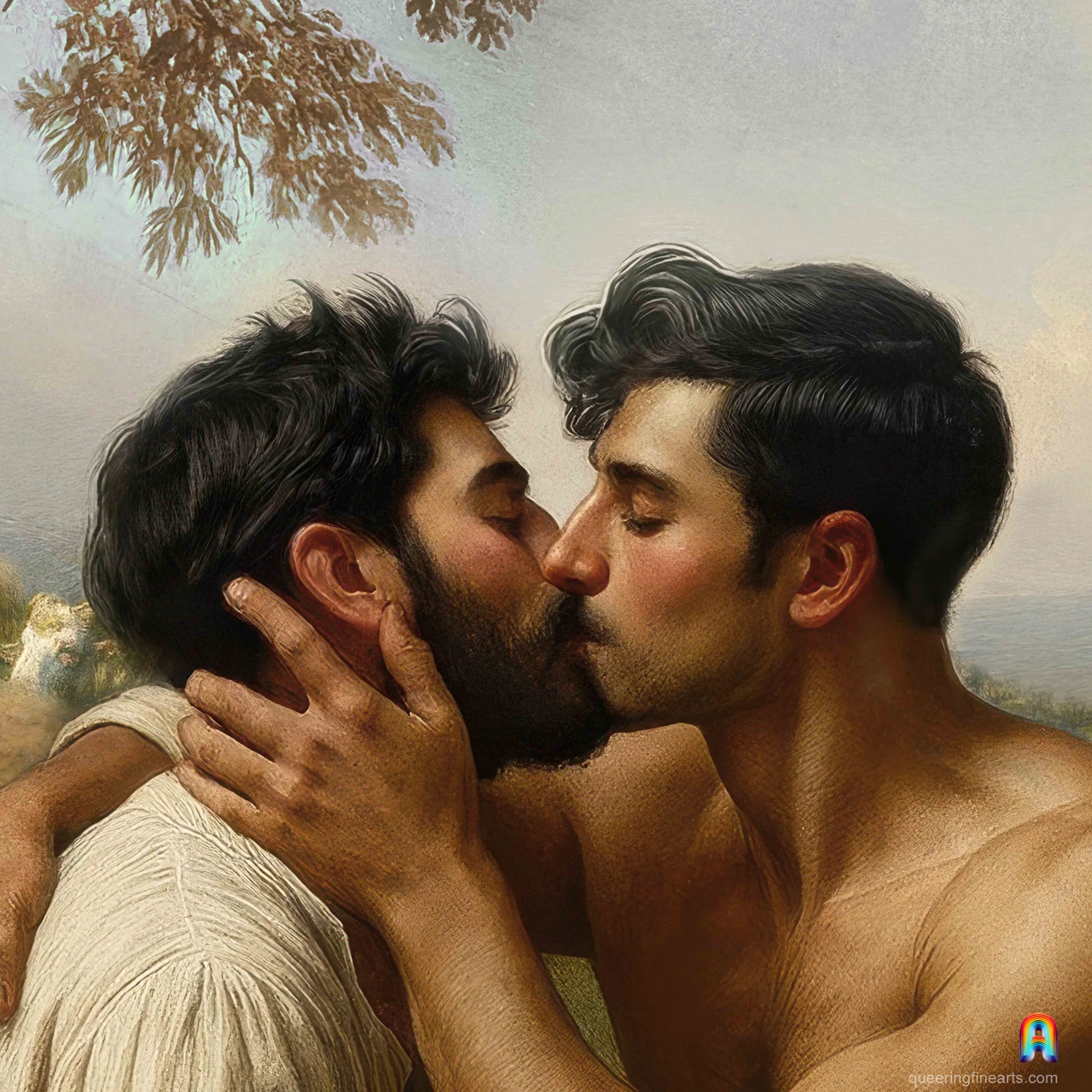

Shepherd's Sweety Pie

Technically, the clarity of the sky and the ceremonial precision in modeling the male body recall academic realism. Yet, this canvas functions as an atelier of desire. The Mediterranean light is not just an illuminator but a sculptor, deliberately carving out the torso that catches the strongest light—the contour of his chest, the gentle expansion of breath. This is a space where queer longing learns to inhabit the very forms historically used to define abstract beauty. The academic study of the body is repurposed from a tool for allegory into a mechanism for authentic, sensual presence. This is where desire is not just depicted, but rehearsed, perfected, and set free under the guise of pastoral idealism⁴.

In Sicily, the German-born photographers Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856–1931) and Baron von Plüschow(1854–1910), together with the Italian Vincenzo Galdi (1871–1961), used albumen prints to place idealized male bodies within sunlit meadows, orchards, terraces and rural paths, creating luminous Arcadian scenes where tenderness and desire could unfold without disguise. L’Ideale follows that lineage, reintroducing queer presence into a visual tradition that once erased it, transforming the rural world into a site of emotional truth, and chosen affection⁵.

Queer Arcadian Iconography

Seen in this light the work functions as a queer Arcadian icon deliberately inserting male male intimacyinto a pastoral vocabulary that once pretended such affections did not exist. The sheep dog, the basket of fruit, the tree canopy, and the luminous horizon all serve as markers of an idyllic world, yet the heart of the painting lies in the quiet kiss shared by the two men.

In doing so, the artist transforms Arcadia, not by adding something new, but by reclaiming what should never have been excluded: queer presence. In this renewed vision of paradise, no Arcadia can be whole without embracing the full spectrum of human desire, welcoming every form of love, intimacy, and connection into its promise of refuge and harmony.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. Smalls, James. Homosexuality in Art. Parkstone Press, 2003.

2. Biscoglio, Francesco. Filippo Palizzi: Tra Naturalismo e Verismo. Napoli: Electa, 1999.

3. Halperin, David M. Before Pastoral: Theocritus and the Ancient Tradition of Bucolic Poetry. Yale University Press, 1983.

4. Lucie-Smith, Edward. The Male Nude: A Modern View. Rizzoli, 1989.

5. Lo Bocchiaro, Giuseppe. Wilhelm von Gloeden: The Realm of the Naked Body. Istituto Geografico De Agostini, 2017.