A Plate from the Service of the Duke of Choiseul-Stainville

Royal Manufactory of Sèvres (green ground, flower reserves, central basin with figures, 1839)

Soft-paste porcelain, polychrome and gilt decoration, circa 1839–1842

Private collection

Tender Glazes

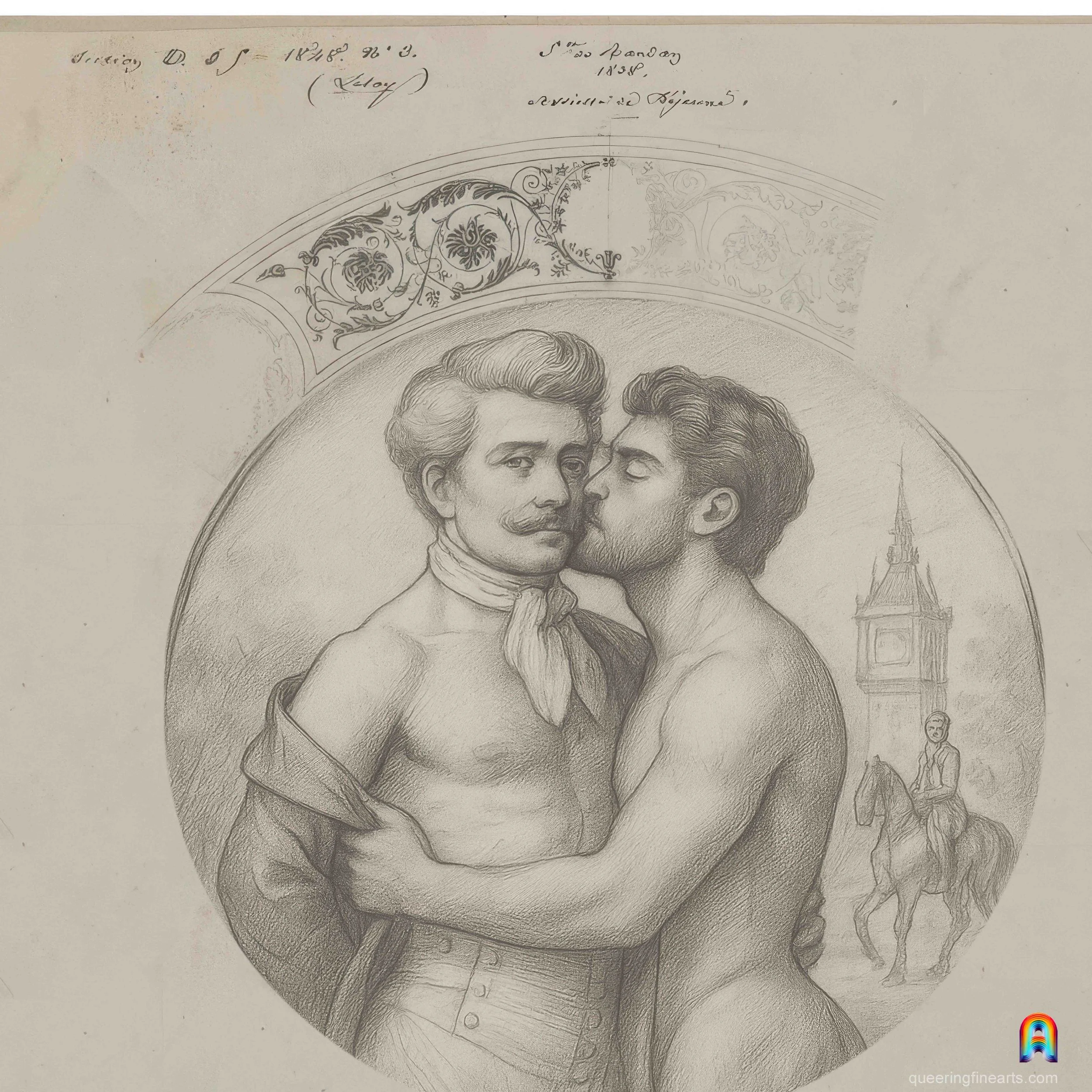

At the center of the rich green marli (the wide, often decorated rim of a porcelain plate) scattered with floral cartouches and gilt scrolls, the scene appears at first unexpected: two men entwined, one already undressed, the other bare to the hips, frozen in a kiss belonging to no official iconography of the nineteenth century. Yet the satiny modeling of the skin, the precise rendering of the slipping draperies and the almost enameled light caressing their torsos point directly to the virtuosity of the painters at Sèvres. Everything unfolds as though the Royal Manufactory had quietly agreed to inscribe, in one of its prestige services, a desire the etiquette of court life kept carefully out of sight.

Theatricalities of the Masculine

On show plates destined for European courts, “bold” subjects did appear on occasion — but always feminized: Venus, bathers, half-draped nymphs. Here, the immaculate surface becomes instead a stage for exposed masculinity: a virility offered up, stretched between near-military posture and amorous surrender. The plate diverts Sèvres’ decorative codes to reveal a clandestine truth: under the July Monarchy¹, masculinity was less a “spectacle” than a constant mise-en-scène — an identity calibrated to the social gaze, traversed by tensions between what one showed and what men actually lived.

In this coded language, the flower-painters — among them Sinsson, whose signature appears on several pieces from the service² — may have taken part in a discreetly audacious shift: introducing into porcelain a narrative official history would never have tolerated.

At Their Plate

The closeness of the two men leaves no room for interpretation: this is a scene of intimacy between male partners, represented where no one would have expected to find it. The court garment slipping off — normally meant to assert rank and representation — becomes a preliminary to the act, a garment the younger partner removes with complete disregard for protocol. His arched hips, his flaunting buttocks and the absence of codified distance state plainly that the two men will soon be lying in the grass, continuing a courtly paradewith members at full salute, one penetrating the other or the other penetrating the one.

The composition even includes a voyeuristic horseman, seemingly more interested in watching — and perhaps joining — their encounter than condemning it. The representation breaks insolently with the visual conventions of its time. At the center of this precious tableware, nothing seeks to divert the meaning: two men who, with assurance, propose an unapologetic etiquette for the decorative arts of the table.

More Legitimate than This Monarchy

In the France of Louis-Philippe — deeply Catholic yet fascinated by refinements of intimacy — porcelain often staged a paradox: a sumptuous art concealing what decorum refused to acknowledge. Galant servicesproduced for European courts allowed themselves the occasional bold touch — but always feminine, always encoded. Never would they have dared depict desire between men.

This plate imagines what should legitimately have existed: a piece discreetly offered to the 4th Duke of Choiseul-Stainville, Armand-Marie-Jacques de Choiseul-Stainville (1785–1854)³, peer of France and habitué of the salons frequented by the House of Orléans. His constant presence in these circles, his noted eleganceand his marked taste for the arts made him a singular figure of the reign.

The Duke of Choiseul-Stainville

Memoirists of the July Monarchy describe a refined, reserved man, deeply attached to male company and whose private life — carefully kept away from public scrutiny — fueled polite society’s murmurs. Unmarried, cultivated, passionate about precious objects, he embodied the kind of personality the period deemed “set apart,” without ever naming what it quietly guessed.

In this context, that someone in the royal entourage might have commissioned a Sèvres service gently subverting the usual iconography for him is hardly implausible: an elegant gift, conceived for someone capable of reading what the polished surface allowed to surface — a piece offered to a man who would have welcomed the scene for what it is: an unmasked, unapologetic depiction of male intimacy.

Something to Dish About

Between censorship and desire, between table décor and the truth of the heart, this piece invents a passage — a luminous breach. An effaced past regains its sheen: the story of love between men, which neither the gilded finesse of Sèvres nor the etiquette of court life should ever have suppressed — and which, since 1839, had been waiting to be seen.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. July Monarchy (1830–1848)

Regime of Louis-Philippe I, characterized by strong bourgeois power, intense court ceremonial and a renewed fascination for luxury decorative arts, including the high production of Sèvres porcelains.

Guillaume Fonkenell, La Monarchie de Juillet (Catalogue du Musée de l’Histoire de France).

2. Sinsson, flower-painter at Sèvres

Jean-Charles-François Sinsson (active early–mid 19th century), one of the prominent peintres de fleurs at the Manufacture Royale de Sèvres. His signature appears on several plates from services produced between 1835 and 1845, often distinguished by finely shaded bouquets and gilt ornamentation.

Tamara Préaud, Le Livre des peintres de Sèvres 1741-1847.

3. Armand-Marie-Jacques, 4th Duke of Choiseul-Stainville (1785–1854)

Peer of France, court figure under the July Monarchy, member of a lineage closely tied to the diplomatic and artistic networks of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His presence in Orléans circles and his noted patronage make him a plausible dedicatee for a bespoke Sèvres service.

Dictionnaire de Biographie Française, entrée « Choiseul-Stainville ».