That Give Delight and Hurt Not

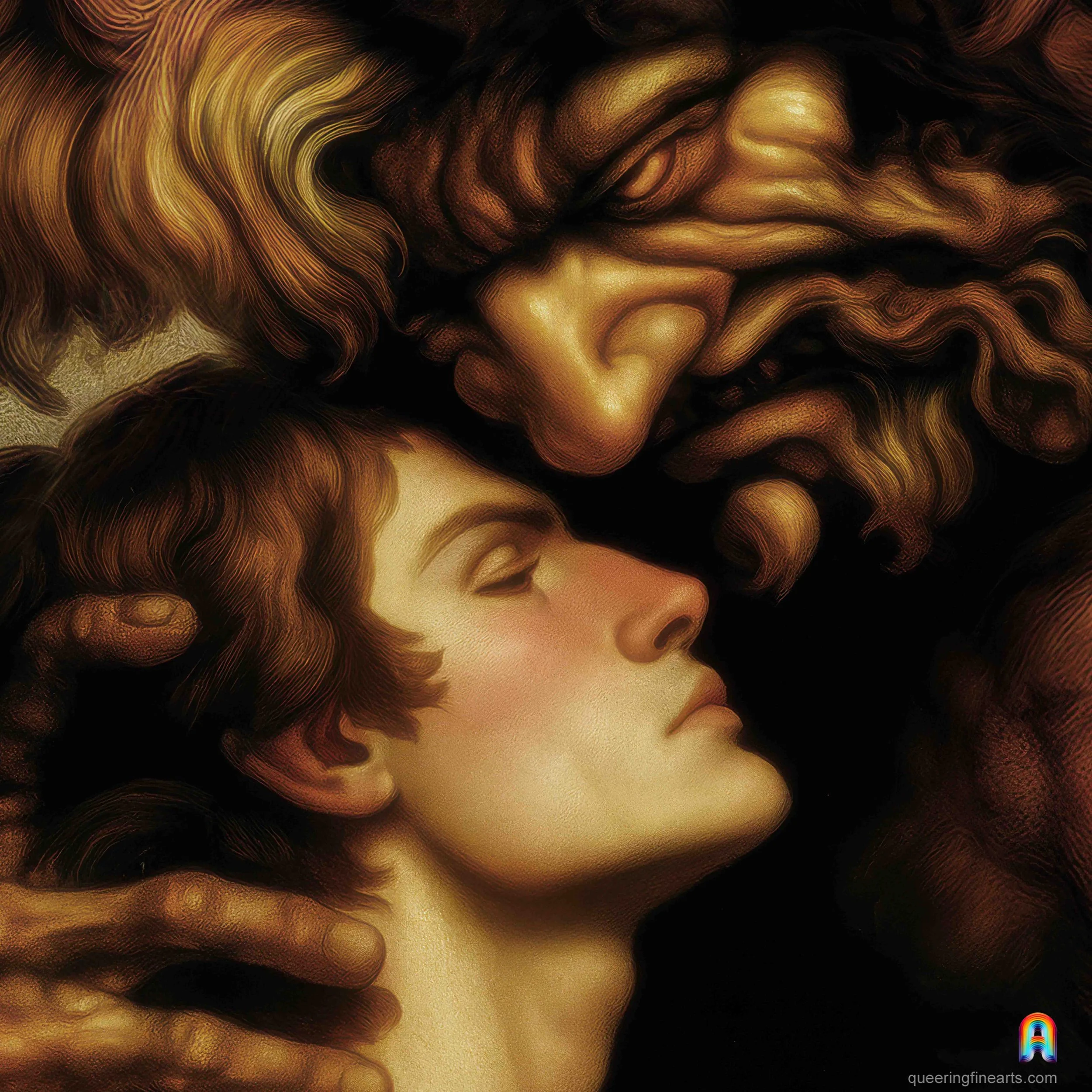

School of Dark Romanticism (after Henry Fuseli)

Oil on panel, c.1820

Collection of an admirer of somber and sentimental works.

“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.”

— William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act III, Scene 2 (Caliban)

A Change of the Sea

Inspired by The Tempest by William Shakespeare¹, this work transposes the relationship between Ferdinand and Caliban through the lens of Dark Romanticism², where beauty, fear, and desire intertwine in tragic tension. The embrace between the radiant prince and the wild creature embodies the fusion of the sublime and the terrible, exploring a desire between a human and the island’s strange son that defies conventional categories.

Desired Otherness

Here, Caliban is no longer the enslaved beast nor the emblem of chaos to be tamed: he becomes the symbol of an otherness fully embraced, of a virile passion that no longer seeks to correct its difference. The young man, surrendered to the creature’s arms, no longer embodies innocence in need of protection but the sublime yielding to the mystery of the other. The bond that unites them transcends humanity itself, celebrating a forbidden intimacy that frees itself from all norms.

Fullness

In this reimagining, attraction takes root in Caliban’s very nature — untamed, sensual, and proud. It seeks neither purification nor civilization, but rather to recognize in this primal force a truth of feeling unknown to the domesticated world. So it must remain: an untamed desire attuned to the beauty of the wild, to what resists measure and reveals the freedom of longing between two male beings, despite the frontier of species.

“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises, / Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.”

In these enigmatic words, Caliban reveals the poetic depth of his being: not the monster feared by others, but a sentient creature attuned to the island’s music, where desire and nature merge. His invitation not to be afraid extends here to the acceptance of an attraction between men as bewitching as it is unsettling.

(To discover a reimagined passage from The Tempest, where the sea still murmurs between two forsaken souls and the storm becomes their embrace, see further on in this publication.)

Unheimlich (The Uncanny)

The golden light and the carnal tension of the bodies recall the universe of Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)³, the Anglo-Swiss painter of nocturnal visions and fevered dreams, whose hallucinatory chiaros-curo defined the visual grammar of Dark Romanticism² — a realm where desire and dread are one, and where beauty is born of disturbance. As in Fuseli’s work, the intimacy between these two male figures is both troubling and fascinating.

The Revelation of the Mage

On a dark spur of rock, Prospero stands over the restless sea. His raised hand suspends the fury of the very elements he himself unleashed. Around him, the light opens like a threshold between two worlds — that of magic and that of men.

But as he commands the spirits of the air to bring back the calm, he understands that his plan to unite Ferdinand and Miranda was but an illusion — an attempt to subject the human heart to the illusion of a calculated order, where every feeling was meant to serve a purpose. In the violence he has just subdued, he perceives his own blindness: the will to correct nature instead of listening to it. As the thunder fades and the sea withdraws, Prospero relinquishes his power.

In the shadow of the forest, far from the turmoil of the waves, a small creature watches the union of Ferdinand and Caliban with serene certainty, as though recognizing in it the true order of the world.

Song of Metamorphoses

The work celebrates a masculine desire faithful to nature — an attraction that does not redeem, but transfigures.

It brings forth the light of immanence: here, to love is no longer to possess, but to dissolve into the other, as foam merges with the sea. The union of Ferdinand and Caliban becomes a shared breath, a return to the unity of all living things, where consciousness falls silent to make way for the sheer joy of being.

In this communion without hierarchy, the world’s beauty reveals itself through continuity: between flesh, earth, sea, and spirit, everything answers, everything calls, everything rises.

“Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

(From The Tempest, I.ii)

Curiosity Piqued?

1. William Shakespeare, The Tempest, c.1611.

2. Dark Romanticism: an artistic and literary movement exploring the fascination with evil, dream, nightmare, and eroticism, opposing enlightened morality with the pull of the unconscious and desire.

3. Henry Fuseli or Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741–1825), Anglo-Swiss painter, draughtsman, and theorist, was one of the key figures of Dark Romanticism. Trained in Zurich before settling in London, he developed an aesthetic of dream and terror blending Gothic imagination with classical sources. His work, nourished by Shakespeare, Milton, and Nordic mythology, explores the shadowy zones of desire, nightmare, and the fantastic.

Fuseli endowed the male body with an intensity rarely equaled — tense, dramatic, sometimes androgynous — making it the vessel of a sublimated erotic energy where fear and fascination merge. This ambiguity, seen in his visionary compositions such as The Nightmare (1781), has led several historians to read his world as the expression of a repressed homoerotic sensibility transposed into the language of dream and disquiet. Through his hallucinatory figures and theatrical light, Fuseli paved the way for Goya, Blake, and the Symbolists, anticipating the psychological and sexual dimensions of the modern imagination.

The Tempest – Song of Metamorphoses

When the ship from Naples wrecked, Ferdinand believed he would die. He wandered alone on the shore, his spirit broken, convinced the sea had taken everything. But the sea, in Shakespeare, always returns what it devours: it gave back to Ferdinand not a kingdom, but another order of the world.

Prospero, observing from afar, believed he was directing his destiny like a puppeteer: he made Mirandaappear, conjured enchantments, laid the trap of love. But Ferdinand, still dazed, first glimpsed another being, half-crawling in the mire, muttering words he did not understand. Caliban.

The Other Encounter

Under the harsh sun, Caliban seemed made of earth and sea-foam. His rough speech was frightening, yet his gestures held the grace of a wounded animal. It was to this blend of shadow and light that Ferdinand suddenly felt bound—not out of pity, but by an obscure recognition.

He accepted Miranda as one accepts a dream fashioned by another—not yet knowing that this dream was not his own.

Awakening

But gradually, the artifice of their meeting impressed itself upon them: they sensed their coming together was less chance than a prepared design. Beneath the tenderness of their exchanges lay the weave of an enchantment, a will foreign to their own.

They perceived then, in each other's gaze, not the promise of a free love, but the reflection of a world governed by reason and obedience, by the power that shapes souls before they even know themselves to be free.

In Caliban, conversely, Ferdinand sensed a knowledge older than Prospero's—a knowledge of matter, of roots, of desire without a name.

The Inverted Trial

Prospero commanded Ferdinand to carry logs to test his love. The young man obeyed, but this labor gradually became a new liturgy: the touch of wood, the sweat, the earth, the silent proximity of Caliban who sometimes helped him in the shadows.

Each log raised, each strip of torn bark was an offering to metamorphosis. Prospero's words—serve—became for Ferdinand words of passage: he served not a master, but the transformation of his own being.

The Other Storm

One evening, near the ruins of a fig tree split by lightning, Caliban placed his hand upon Ferdinand's, a gesture that was neither tenderness nor violence but the world reclaiming its rights; Ferdinand felt in this grasp the end of hierarchies, the union of prince and monster, of reason and flesh. The love born there had no human language; it was elemental, telluric; this was the true tempest—not the one Prospero had raised upon the sea, but the one that crashed down within the young man's heart.

The Essence of Things

When the sea grew calm, Prospero saw the order he had sought to preserve collapse.

Ferdinand no longer desired to reign, nor to return to Naples, nor to marry Miranda. He remained on the island, half-wild, speaking a language he invented with Caliban, a language made of salt and wind.

And Miranda, in all this...

It was then that Miranda spoke. She had understood that her father's world—founded on reason, will, and the magic of command—was reaching its end. She asked Prospero to grant her the freedom to act, to entrust to her the destiny of the island and those who lived there.

Mistress of Her Fate

She no longer wished to be the instrument of his designs, but the heir to a new power. The island was to be no longer a territory of control, but a space for listening. In her voice resonated a wisdom born of solitude and connection with nature.

Facing her, Prospero understood he had no choice but to consent. He lowered his staff and recognized in his daughter the promise of another world: a new sovereignty, non-hierarchical, founded on reciprocity between the human and the living.

In ceding his magic to her, he ended magical domination and consecrated the advent of an intuitive, pacified power, where magic no longer serves to constrain, but to connect.

They then sent envoys to Naples and Milan to restore harmony between powers once divided.

The New Order

Their message spoke less of conquest than of reconciliation, of the promise of a world delivered from the chains of resentment and absolute power.

Meanwhile, Prospero, having laid aside his magic and his wrath, remained on the island.

There, by the edge of the sea, he spent serene days, watching over the breath of the wind and the speech of the waves—a silent witness to a world finally reconciled with itself.

Q

In the Wake of The Tempest

ACT V, SCENE II — A Grove after the Tempest

A clearing. The air is thick with damp earth. CALIBAN gathers branches; FERDINAND enters, unarmed, watching him.

FERDINAND

Stay, creature of the isle—thou mov’st as though the wind obey’d thy limbs.

When first I saw thee, wrath possess’d my soul;

But now—methinks that wrath is gone, dissolv’d,

Like foam upon the sea.

CALIBAN

Mock not, young lord. My shape offends thine eyes.

I am earth’s spawn—half wave, half mire.

Thy father’s men would whip me for my shadow.

FERDINAND

Thy shadow is more human than their light.

There is in thee some music I would learn—

A rough, sweet note that wakes my blood.

CALIBAN

Ha! Music? From this tongue that knoweth naught but curses?

I spit at heaven, yet thou hearest song?

Beware, fair youth—my heart is salt and fang.

FERDINAND

Then let me taste the salt, and fear the fang.

If sin it be to look on thee with wonder,

Then let my sin grow bold and take thy hand.

(He reaches toward him. Caliban trembles, torn between shame and desire.)

CALIBAN

Touch not—thou know’st not what thou wak’st in me.

The storm that broke thy ship still roars within my blood.

FERDINAND

And in mine too. The same sea claim’d us both—

Perhaps we are its sons.

(Silence. Caliban steps nearer; the wind subsides.)

CALIBAN

If I be monster, then art thou half the same.

For I behold in thee the beast made gentle,

And in myself, the man unchain’d.

FERDINAND

Then let the isle be witness—

That two lost souls may find one shape in love.

(They stand facing each other, hands nearly touching as thunder murmurs far away.)

CALIBAN

Hark—the storm returns.

FERDINAND

Nay, friend—it is but our hearts replying.

(The light fades as they join hands. The sound of the sea rises.)