The Covenant of David and Jonathan

Workshop of Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651)

Oil on canvas, circa 1630

Private collection

Luminous Alliance

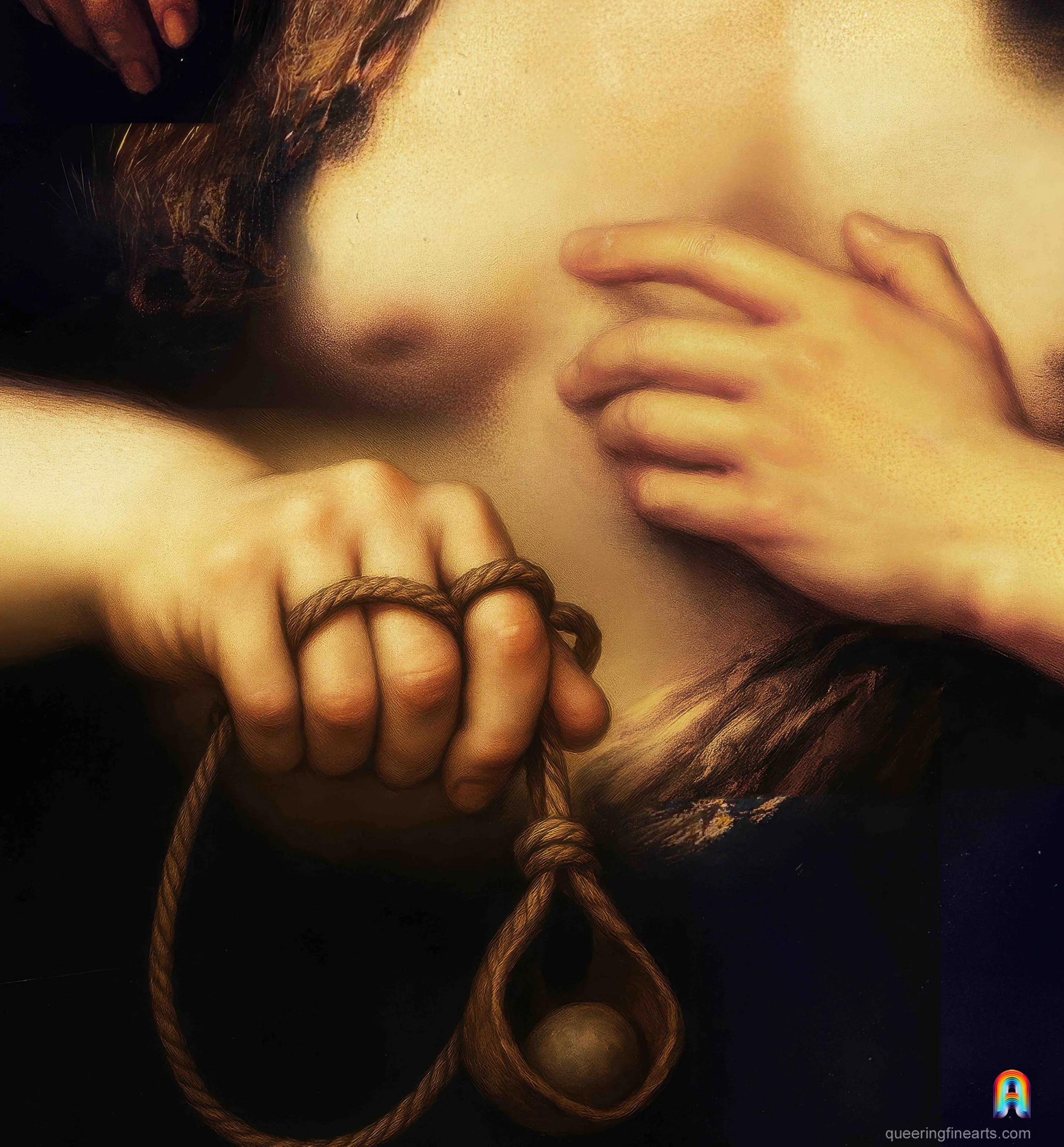

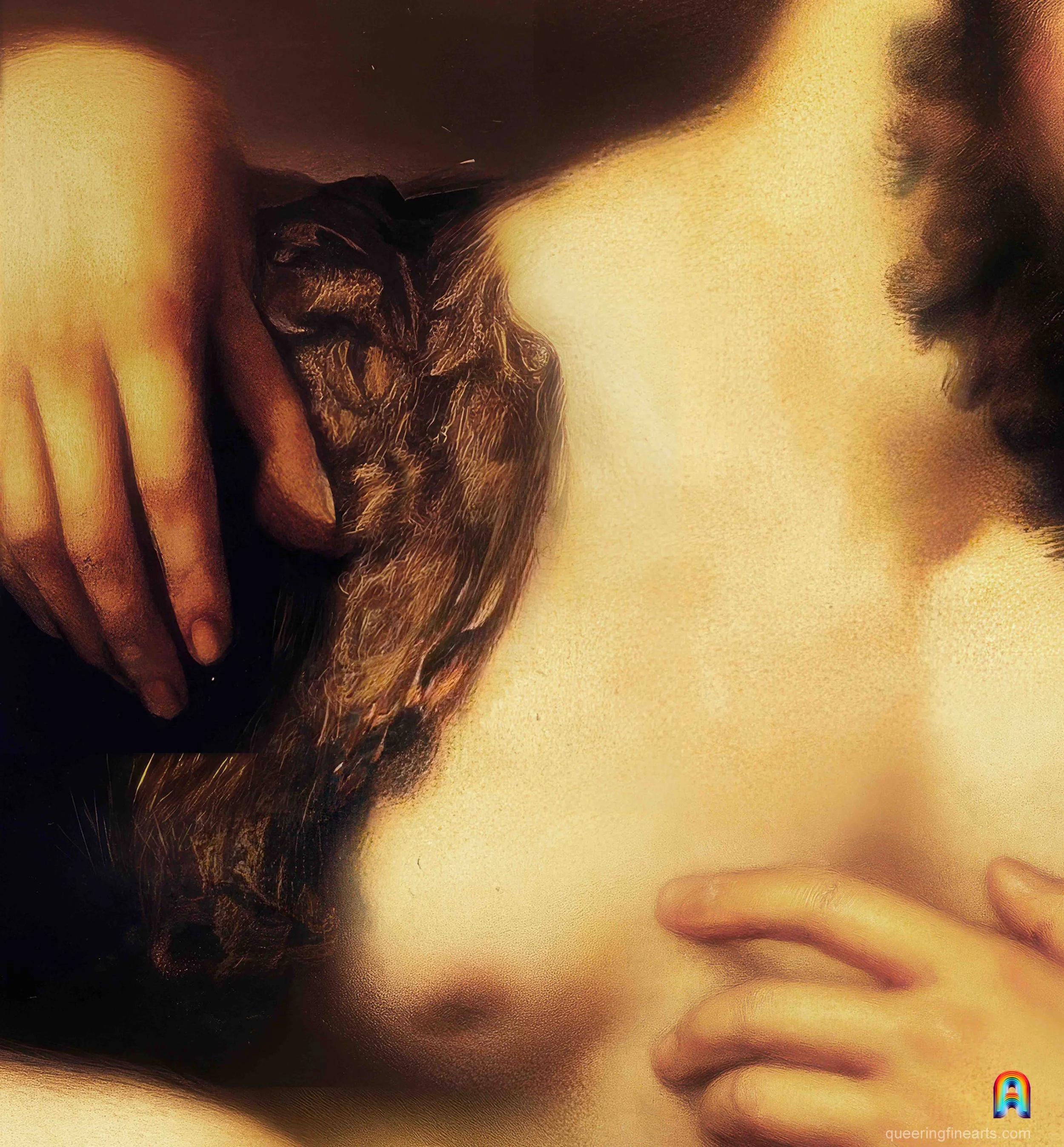

The painting brings together two male figures of distinct origins: on the left, David—the shepherd who defeated Goliath and the future king of Israel—half-nude beneath a dark drapery, still holding in his hand the sling that brought him victory; on the right, Jonathan, his prince and ally, dressed in a purple mantle and crowned with plumes.

Their faces incline toward each other, a hand rests upon a chest, and the golden light enveloping their bodies conveys a solemn intimacy. Through the chiaroscuro, the vigor of the modeling, and the contained sensuality of the gesture, the work belongs to the spiritual and carnal tradition of the Utrecht school.¹

Matter and Grace

The workshop of Abraham Bloemaert, active in Utrecht during the first half of the seventeenth century, was one of the most prolific centers of Dutch painting.² Trained in the mannerist style but matured through contact with Caravaggism, Bloemaert and his pupils developed a language in which warm amber light, dense impasto, and a balance between idealization and realism served a deeply humanized religious iconography. Their supple line and tender modeling infused biblical subjects with earthly warmth, far removed from the austerity of northern Protestant art.

Flesh and Fervor

Artists of his circle, like the master himself, drew freely on stories from the Old Testament—tales of patriarchs, prophets, and kings in which faith mingled with flesh, and human feeling illuminated the relation to God.³ Within this tradition, the representation of David and Jonathan acquires a singular force. It depicts not war or kingship, but a moment of union. The episode originates in the First Book of Samuel: “The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul” (1 Sam 18:1). Repeated several times, this verse finds here a pictorial translation of rare intensity: the hand upon the chest and the nearness of their faces become the language of a covenant of hearts.

A Prince and a Shepherd

This bond unfolds at a turning point of destiny. Jonathan, heir to Israel’s throne, recognizes in David—a shepherd turned hero—the man secretly chosen by God to reign. Rather than defending his right to the crown, he accepts this divine design and joins it out of love and loyalty. Their alliance is born at the meeting of two glories: Jonathan, already victorious over the Philistines, and David, newly crowned by triumph over Goliath.⁴ Two men whom everything once separated now recognize each other as equals in fervor and courage—one embodying the nobility of renunciation, the other the grace of divine favor. In the painting, their brotherhood becomes visible: the hand laid upon the chest is no longer a sign of allegiance but a gesture of restrained emotion, where tenderness outweighs hierarchy.

Tenderness

In Scripture, the friendship between David and Jonathan is sealed by a covenant of love and loyalty: “Jonathan made a covenant with David, because he loved him as his own soul. He took off the robe that he wore and gave it to David” (1 Sam 18:3–4). Later, at their parting, “they kissed one another and wept with each other” (1 Sam 20:41). And when Jonathan dies in battle, David laments: “I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan; your love to me was wonderful, surpassing the love of women” (2 Sam 1:26). These verses, unusually tender within the Scriptures, reveal an affection that seventeenth-century painters still rendered under the guise of heroic friendship.⁵

Contemporary Readings

In recent decades, several scholars have revisited this bond through the lens of queer theory. Tom M. Horner (Jonathan Loved David: Homosexuality in Biblical Times, 1978) was the first to argue that the vocabulary used in these passages belongs to the semantic field of conjugal affection. Susan Ackerman (When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David, 2005) explored the erotic and spiritual dimensions of the relationship, showing that in ancient culture, male love could signify both a union of souls and of bodies. Martti Nissinen (Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, 1998) situated David and Jonathan among the rare biblical pairs whose emotional intensity transcends moral categories.⁶

Anthony Heacock (Jonathan Loved David: Manly Love in the Bible and the Hermeneutics of Sex, 2011) applied a queer reader-response approach, interpreting their bond as a sacred yet socially transgressive love.⁷ K. C. R. Tyson (A Cultural Study of the David and Jonathan Relationship in 1 Sam 18, PhD thesis, Durham University, 2013) examined the same narrative from a cultural and gendered perspective, reading it as a complex construction of masculine intimacy and loyalty.⁸ These modern interpretations do not reduce the scene to a physical act but restore to ancient male friendship its full charge of emotion, fidelity, and sublimated desire.

Serenity Before the Trial

In this canvas attributed to Bloemaert’s workshop, time seems suspended between two gazes. The red of the mantle evokes at once passion and blood, royalty and promise. Everything breathes recognition and calm before the ordeal, as though the painter sought to capture the harmony of hearts before the turmoil of arms.

And one recalls David’s lament for Jonathan:

“You were most dear to me; your love to me was wonderful.”

(2 Samuel 1:26)

In the stillness of the painter’s gesture, that verse becomes image—a brotherhood so profound it touches the mystery of love itself.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. Joaneath Spicer, Masters of Light: Dutch Painters in Utrecht during the Golden Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

2. Abraham Bloemaert, Schilder-Boeck (Utrecht, c. 1625), quoted in Marcel G. Roethlisberger, Abraham Bloemaert and His Sons (Doornspijk: Davaco, 1993).

3. Gary Schwartz, The Dutch Biblical Painting in the Seventeenth Century (Maarssen: Schwartz, 1985).

4. The First Book of Samuel, chaps. 14–18, The Jerusalem Bible (Paris: Cerf, 1998).

5. The Second Book of Samuel, chap. 1, v. 26, ibid.

6. Tom M. Horner, Jonathan Loved David: Homosexuality in Biblical Times (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1978); Susan Ackerman, When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998).

7. Anthony Heacock, Jonathan Loved David: Manly Love in the Bible and the Hermeneutics of Sex (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2011).

8. K. C. R. Tyson, A Cultural Study of the David and Jonathan Relationship in 1 Sam 18 (PhD diss., Durham University, 2013).