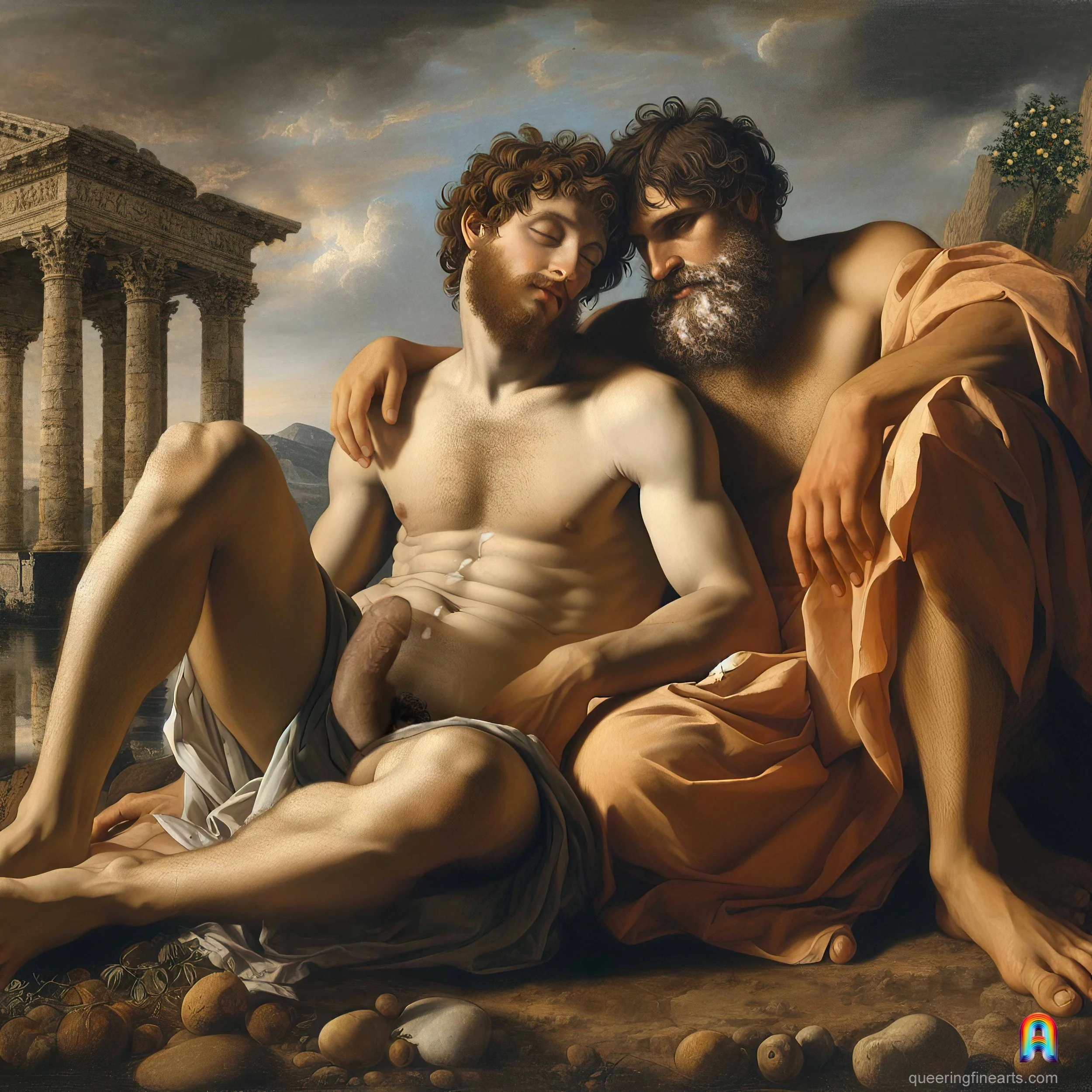

Rest After the Triumph

Attributed to the circle of Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506)

Tempera on panel transferred to canvas

Private collection, Italy

Intimacy and Masculinity in the Renaissance

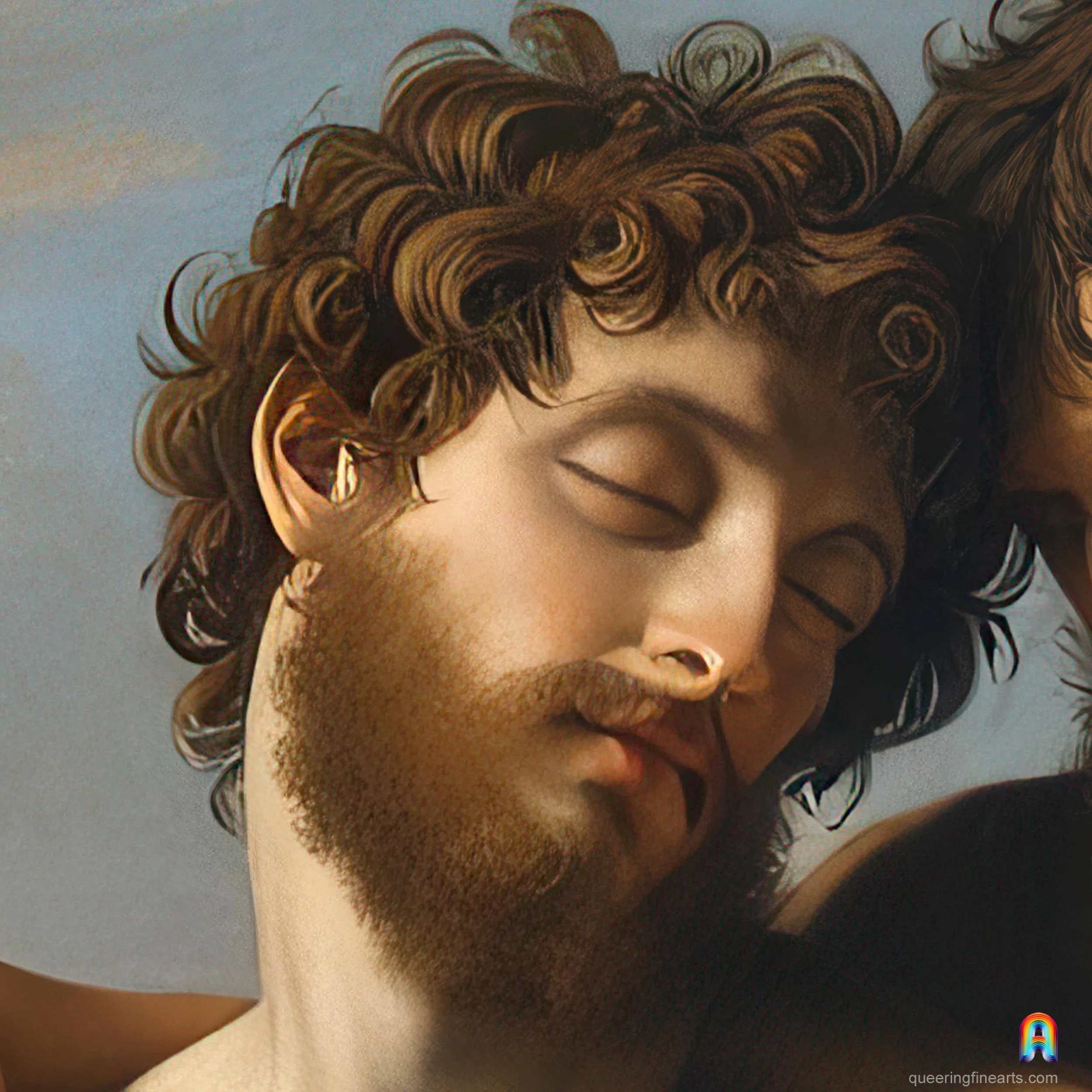

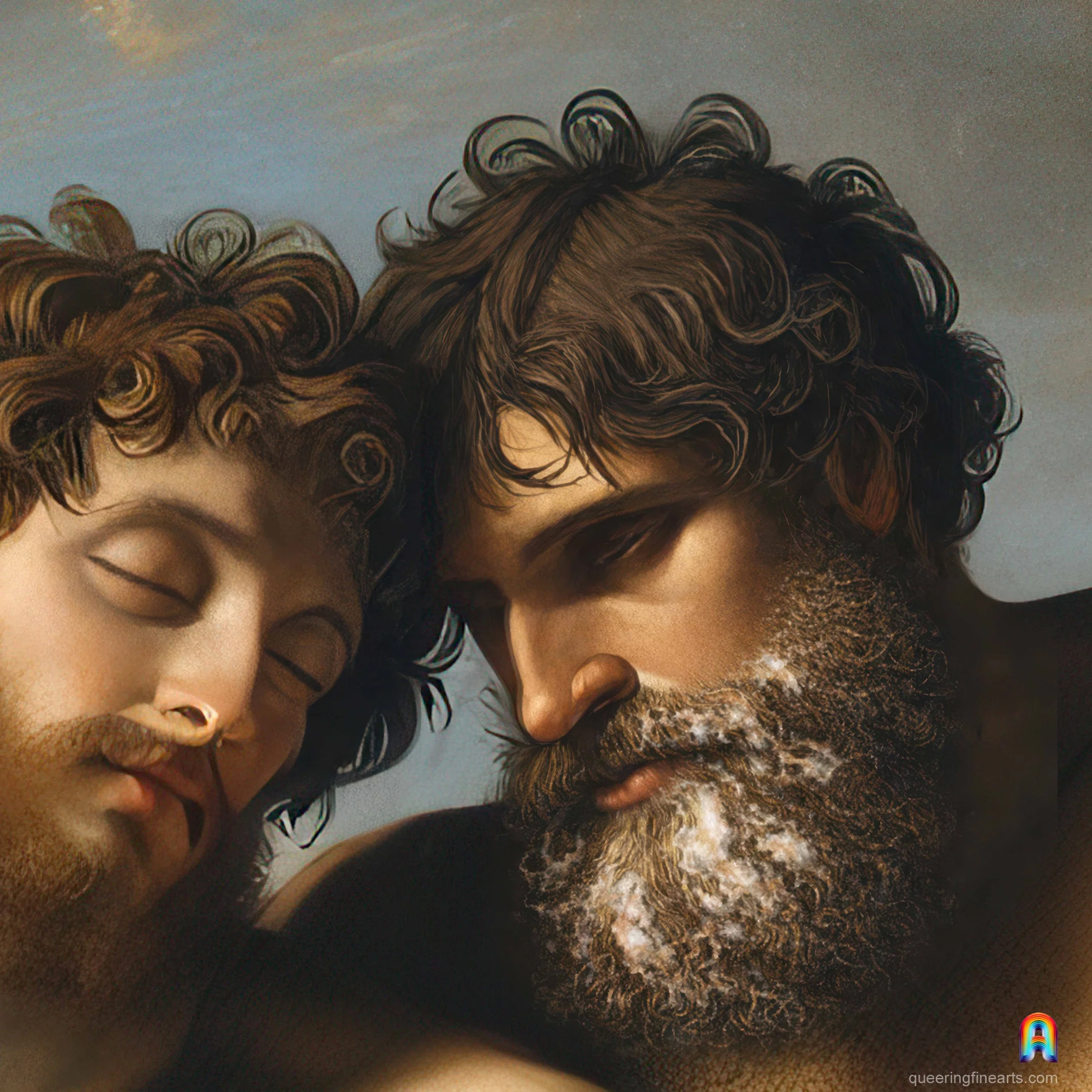

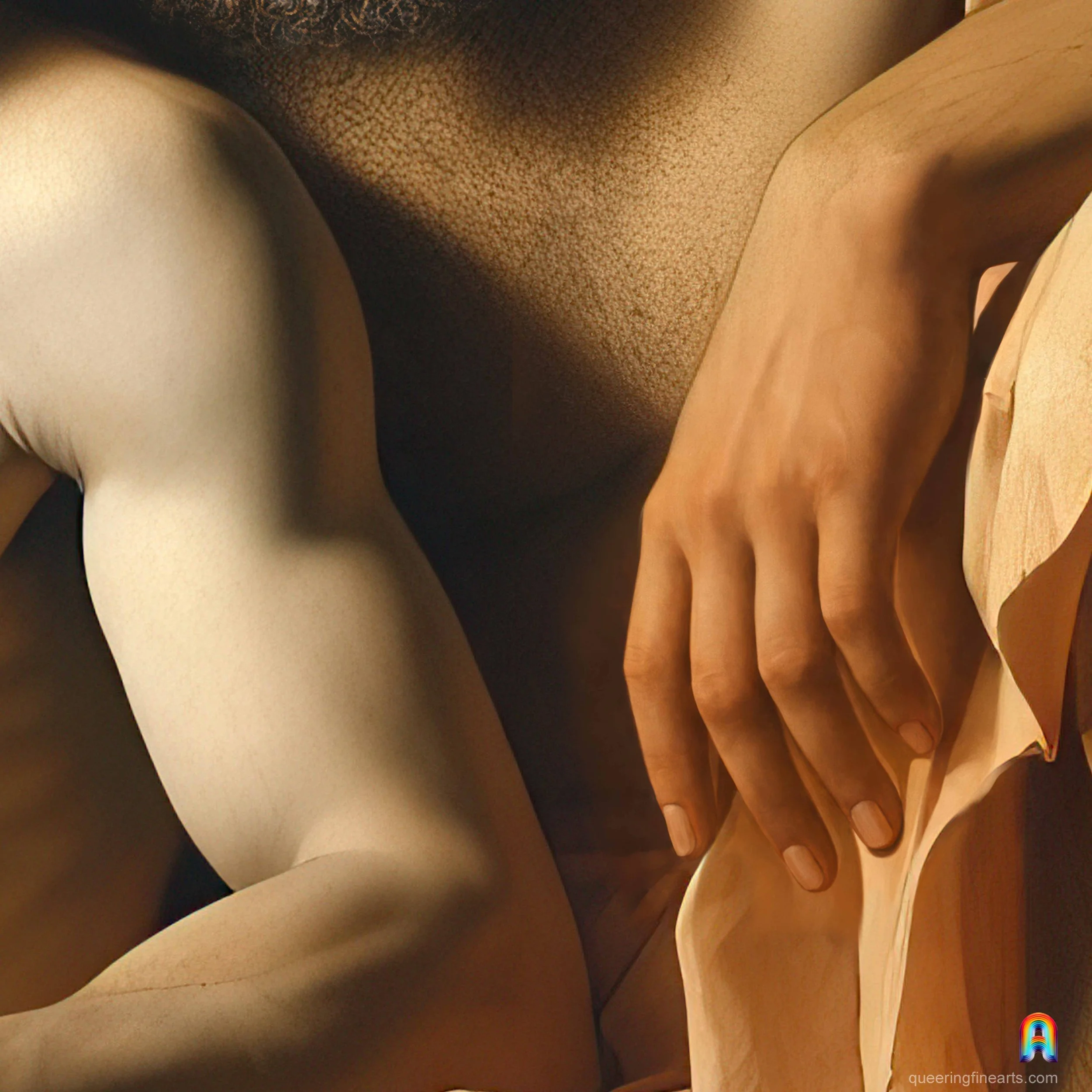

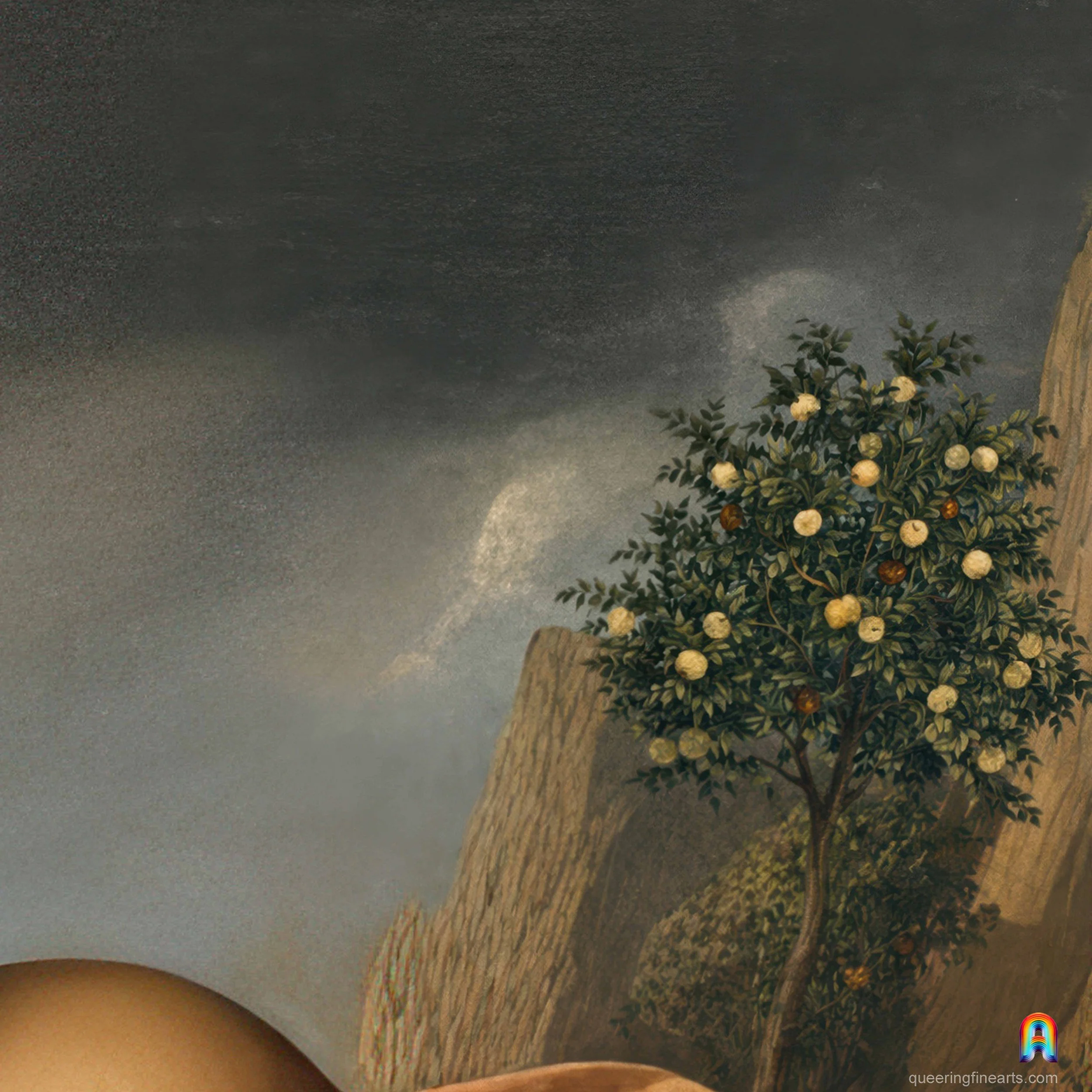

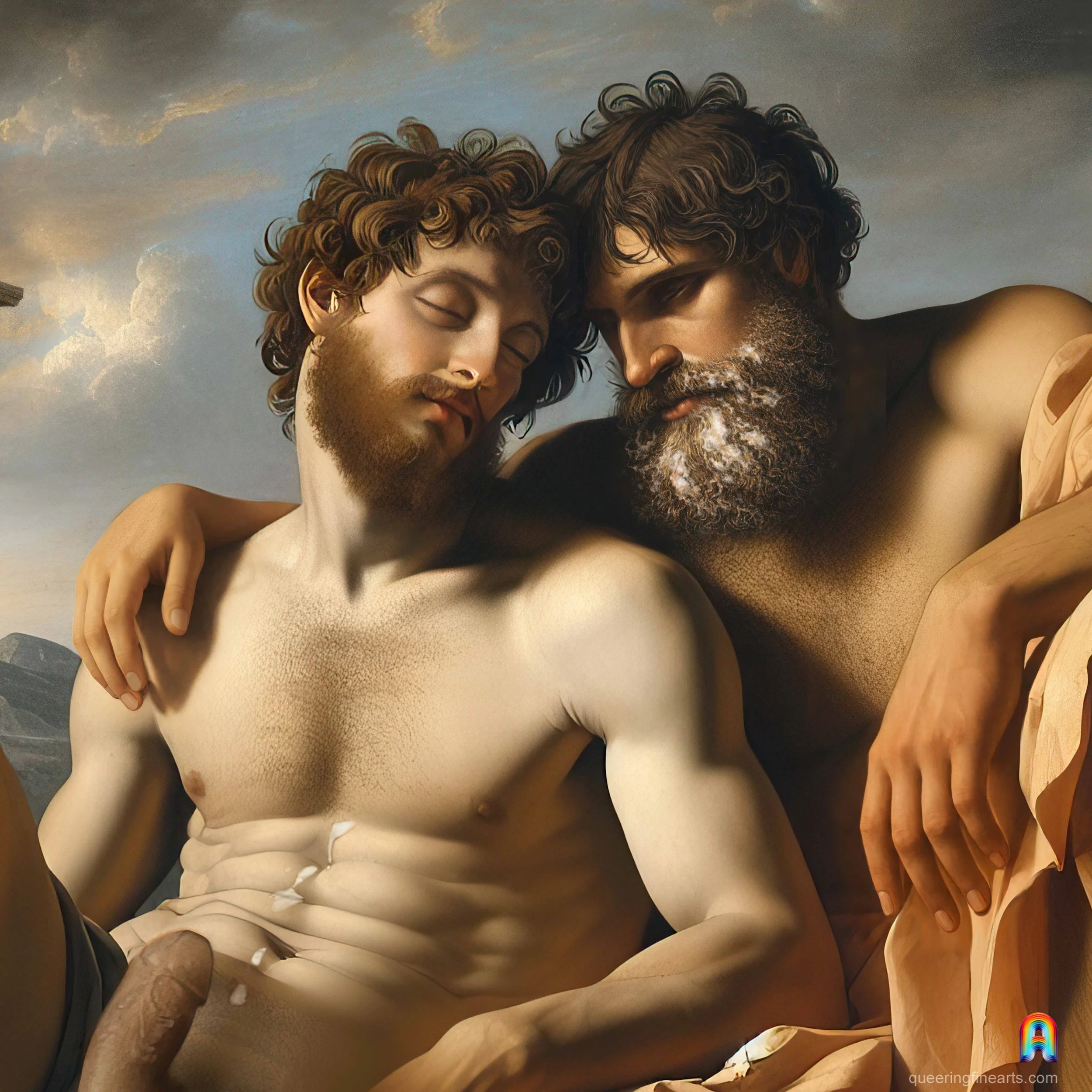

Rest After the Triumph depicts two adult men reclining in the foreground of an antique landscape. Their bodies, of different complexions, still close to one another, touch at the shoulders, hips, and legs, in a posture of deep relaxation. On the chest of one appears a trace of semen recently ejaculated from his triumphantly displayed erect penis. The beard of the other is also covered with semen, suggesting that his face was close to his companion’s member at the moment of ejaculation¹. The draperies are partially loosened, revealing a measured and credible male nudity, without heroic emphasis. Both men display a calm, focused expression, as if after an intense exertion. The setting is composed of rocks, fragments of ancient architecture, and a dry ground, evoking an austere Mediterranean environment. The palette favors earthy tones, ochres, browns, and muted greens, with a clear light that accentuates the volume of the bodies and their weight in space. The composition privileges stability, reinforcing the idea of rest and fulfillment. The work is attributed to an assistant or disciple active in Andrea Mantegna’s workshop in Mantua toward the end of the fifteenth century, and would have been produced for Francesco II Gonzaga, within the context of a private commission. It is worth recalling that Mantegna was at that time a leading artist, painter and engraver of the Italian Renaissance, renowned for his innovative use of perspective and his major influence on the evolution of European painting².

Virile Flesh in Mantegna’s Workshop

The attribution to an assistant of Mantegna allows the work to be situated within a historically credible zone. Mantegna’s workshop transmitted a vision of the male body grounded in density, gravity, and proximity to Antiquity³. Assistants drew from a relatively austere repertoire: rocky landscapes, sober compositions, compact male figures, present and corporeal without emphasis. This visual language already offered fertile ground for a homoerotic reading, even when the subject remained officially heroic, religious, or mythological. The soldiers of the Triumphs, the athletic saints, and the virile companions formed a constellation of bodies offered to the gaze, desirable, conceived within a masculine continuity.

A Coded Male Intimacy in Mantua

In this context, a commission for Francesco II Gonzaga appears coherent. Francesco II ruled within a court culture dominated by male proximity. A condottiere and military leader, he lived surrounded by captains, pages, squires, and young men sharing the same spaces, the same campaigns, and the same makeshift beds. Masculinity circulated there as a central value, founded on loyalty, the body, physical closeness, and virile camaraderie⁴. In such an environment, desire between men found implicit forms of expression, supported by ancient models such as Achilles and Patroclus, Alexander and Hephaestion, and warrior couples united by flesh and by combat. A private work showing two men after lovemaking fits naturally within this cultural continuity.

The Gonzaga Court and the Intimacy of Bodies

This openness, still measured under Francesco II, reached a new intensity under Federico II Gonzaga. Federico inherited a Mantua already shaped by Mantegna and his disciples, but he pushed this tradition toward a freer exploration of the male body. The commissions given to Giulio Romano (1499–1546), a painter renowned for his powerful and dramatic style, notably at the Palazzo Te, testify to an assumed gaze upon male flesh, nudity, and bodily proximity⁵. The rooms decorated for Federico present numerous young men, nude or partially clothed, engaged in mythological scenes in which strength, sensuality, and physical contact occupy a central place. Masculinity becomes a learned spectacle, reserved for private spaces, legible to a cultivated circle.

Accentuation of Homoeroticism

Rest After the Triumph thus finds its exact place within this chronology. A pivotal work within the Mantuan context, it emerges at a moment when homosexuality was already circulating in Italian courts in coded forms, and it takes part in an evolution that would gain greater visibility under Federico II. It functions as a point of passage, specific to the tradition inherited from Mantegna, between a humanist restraint and a more direct affirmation of male desire at the beginning of the sixteenth century⁶.

Intimate Fulfillment

The title condenses this double reading. The triumph refers to military victory, public glory, and the Roman heritage that structures the Gonzaga imaginary. It also refers to an intimate fulfillment, that of lovers who have made love, who have shared their seed, and who have together experienced a carnal victory. Rest then becomes a state of equilibrium. Bodies relax after the effort of battle as they do after the intensity of the sexual act. Proximity, trust, and mutual abandonment embody a masculinity fully achieved and fully lived.

The Grandeur of an Accomplished Male Relationship

The work thus asserts that masculine greatness is not limited to conquest or domination. It includes the capacity to give oneself to another man, to share pleasure, and to recognize in a similar body a form of continuity. Rest After the Triumph situates itself within the tradition of the Renaissance while extending it. It uses its codes, references, and historical limits to open a space of visibility in which the relationship between men finds a coherent, dense, and enduring pictorial form.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. James M. Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1986.

2. Keith Christiansen, Andrea Mantegna, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.

3. Evelyn Welch, Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995.

4. Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996.

5. Manfredo Tafuri, Giulio Romano, Milan, Electa, 1989.

6. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. I, The Will to Knowledge, Paris, Gallimard, 1976.