Champagne with Charlus

Oil on canvas, early twentieth century, circa 1900–1915

Private collection, Paris

A Politics of Celebration

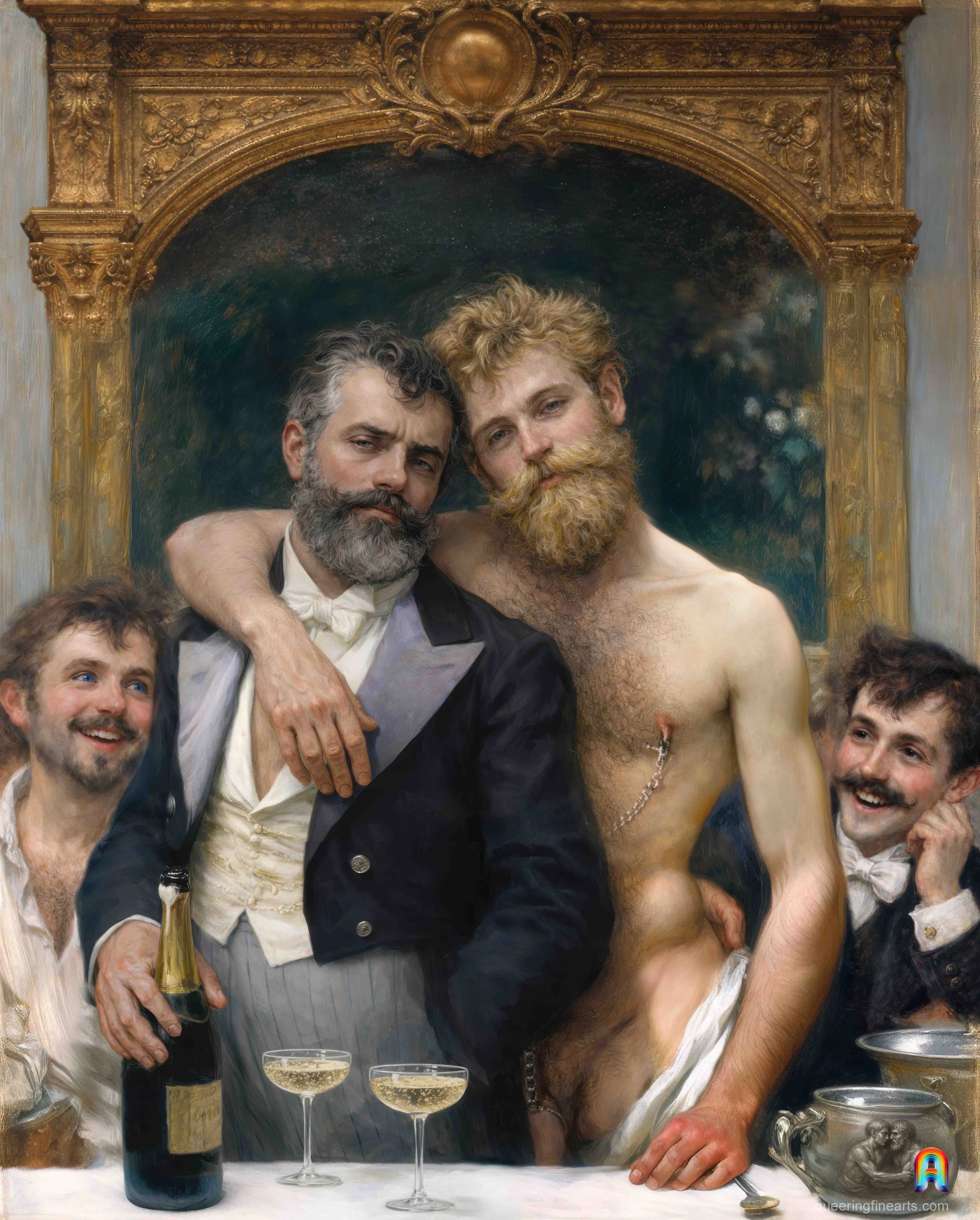

The scene depicts Baron de Charlus, a central character in In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1871–1922)¹, at the heart of a fashionable New Year’s Eve gathering, surrounded by young men assembled around a table where champagne flows freely². Bodies draw closer, gestures become familiar, at times protective, at times overtly offered. Full coupes, an opened bottle and complicit smiles establish an atmosphere of suspended festivity, at once elegant and deliberately troubling, where shared intoxication, acknowledged pleasure and collective joy disregard social convention³.

A Proustian Moment of Freedom

Around Charlus, the male figures form an ambiguous gallery in which friendships and paid presences intermingle⁴, without any clear boundary between them. The partial nudity of certain bodies, set against the evening dress of other guests, asserts the carnal dimension of this New Year’s Eve celebration, while the refined décor and the ritual of champagne anchor the scene within a world of privilege and diverted social codes⁵. The chain linking a nipple clamp to a cock ring clearly affirms the subversive nature of the sexual practices on offer at this New Year’s Eve gathering. The whole celebrates a nocturnal moment of freedom in which pleasure, wealth and affection coexist with apparent ease.

Time Granted to the Night

Do you hear the bursts of laughter, followed by low-voiced exchanges? The adjoining salon is animated by a joyful and lascivious gathering. Baron de Charlus is hosting a party there. Champagne circulates freely, coupes are refilled as soon as they are emptied and the handsome young men who have joined him speak little of serious affairs. What matters is lingering, savouring the company and staying when others slip away. Bodies move closer, gestures grow familiar, sometimes protective, sometimes openly offered. For a few hours, the night suspends convention⁶.

Pleasure as Social Deviation

Baron de Charlus is one of the most complex and audacious characters in In Search of Lost Time. A flamboyant aristocrat, excessive, alternately domineering and vulnerable, he embodies a form of homosexuality that is both visible and constantly monitored by the social rules of the Belle Époque⁷. Through him, Proust gives substance to a male sexuality shaped by rituals, staging and power games, directly nourished by what he himself observed and lived⁸. Charlus appears to favour young men of modest origins, soldiers or labourers. He shows a particular taste for French Canadians, valued for their direct virility, their cheerful availability and their distance from Parisian worldly hypocrisy⁹. These preferences outline a world of pleasure in which social and linguistic difference becomes a source of attraction and freedom.

Masculine Symbolism of Champagne

Within Western social codes of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, champagne is embedded in a symbolism strongly marked by masculinity. The traditional gesture of opening the bottle, held between the thighs and directed upward along the body, was historically conceived as an act appropriate to men, as it mobilizes implicit sexual imagery associated with virility. The elongated shape of the neck, the internal pressure, the moment of release, and the sudden projection of liquid were interpreted in the social and moral discourses of the period as phallic and ejaculatory metaphors, with the foaming itself contributing to this analogy. These associations helped establish the opening of champagne as a masculine ritual act, linked to power, ostentatious expenditure, and performative masculinity. Champagne thus becomes a symbolic object in which social representations of sex, power, and virility crystallize, far beyond the realm of simple celebration.

The Hour of Effervescence

Champagne, for Charlus, is never merely a sign of wealth. It arrives at the precise moment when the evening changes rhythm, when laughter rises, when one decides to stay a little longer, when the party truly begins. A drink of celebration and acknowledged expenditure, it belongs to a perfectly regulated aristocratic ritual while opening a tolerated nocturnal space in which male proximity can take hold without needing to be named¹⁰. Accepting one more glass, prolonging the evening, letting the hour slip by, these are the conditions through which encounters and pleasures are made possible that would have no place in full daylight. Raising one’s coupe is not merely to toast, it is to declare that the night belongs to those who remain.

A Nocturnal Sociability

This atmosphere runs through the novels from beginning to end. Champagne appears at dinners and receptions among the Guermantes at the precise moment when the meal draws to a close and conversation becomes freer, livelier and more charged with innuendo¹¹. It also circulates at the Parisian suppers Charlus frequents or hosts, where receiving guests and letting the evening stretch allows one to hold on to the company and savour their presence. In Sodom and Gomorrah, Charlus’s encounters always unfold within this luxurious nocturnal sociability, shaped by extended time, circulating bodies and shared pleasures, even when champagne is not named on every page¹². Proust’s analysis reveals how celebration, night and a carefully controlled excess become the very conditions of a possible freedom.

Escaping the Social Yoke

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, alcohol in general and champagne in particular as the festive drink par excellence occupied a very real place in sociabilities now recognised as historical centres of LGBTQ+ cultures¹³. In Parisian salons on the Right Bank and in Montmartre, semi-private spaces where aristocrats, artists and writers crossed paths, it accompanied a controlled loosening of conventions and enabled a coded circulation of desire. Marcel Proust describes with remarkable precision these rituals in which homosexuality and champagne coexist within a culture of allusion, tact and time granted. In the cabarets of Montmartre, notably at Le Chat Noir, champagne becomes the drink of night and spectacle, marking entry into a space where the moral hierarchies of daytime lose their hold¹⁴, frequented by men attracted to men, independent women and figures at the margins of the dominant social order.

License and Modernity

At the heart of European artistic circles, champagne accompanies a claimed modernity shaped by wit, self-staging and nonconforming desires, embodied in particular by Oscar Wilde¹⁵. Among women, the salon of Natalie Clifford Barney offers an attested example of lesbian and bisexual sociability in which champagne accompanies an assumed amorous and intellectual freedom¹⁶. In contexts often marked by repression and the threat of scandal, toasting becomes a discreet language, a rite of recognition and a gesture of social persistence. The link between champagne and LGBTQ+ cultures is therefore neither a cliché nor a late metaphor, as evidenced by fin-de-siècle supper accounts, but a precise social history rooted in identifiable places, practices and figures.

Midnight as a Point of Shift

New Year’s Eve occupies a singular place in the history of LGBTQ+ communities precisely because it concentrates, in a single night, gestures of freedom ordinarily monitored or forbidden¹⁷. Midnight authorises embraces, nocturnal celebration, playful cross-dressing, collective intoxication and a symbolic suspension of the moral order. In societies where homosexuality remains criminalised or severely stigmatised, this parenthesis renders queer visibility both more possible and more exposed. Police repression therefore manifests itself with particular brutality, yet this very violence has often produced the opposite effect, provoking new awareness, solidarities and lasting advances.

From Oppression to Claim

A foundational example takes place at the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles during the 1966 New Year’s Eve celebration¹⁸. At the stroke of midnight, undercover police officers assault and arrest patrons for the simple act of kissing someone of the same sex. The event deeply shocks the community not only through its violence but through the public and symbolic nature of the attack, occurring precisely at the moment when the celebration promised a new beginning. Rather than retreating, those affected organise a peaceful and structured demonstration a few weeks later. It is now recognised as one of the first documented public LGBTQ+ protests in the United States. The New Year’s Eve celebration, meant to be a moment of submission to order, thus becomes the point of departure for a collective and visible assertion.

A Legal Turning Point

In San Francisco, a year earlier, New Year’s night plays an equally decisive role with the ball organised at California Hall in January 1965 by the Council on Religion and the Homosexual¹⁹. Although the event was legally authorised, police deploy a massive presence, intimidate participants and carry out arrests, even targeting lawyers present to defend the guests’ rights. Far from marginalising the movement, this repression provokes a media scandal and a major legal turning point. It helps structure a solid legal defence and strengthen alliances among activists, jurists and progressive institutions. Here again, New Year’s Eve acts as a catalyst. By exposing the injustice of repression within a festive and peaceful context, it accelerates a dynamic of emancipation rather than suffocating it.

A Toast to Equality

These episodes show why New Year’s Eve returns so frequently in the history of LGBTQ+ struggles²⁰. It is not merely a symbolic date but a moment when collective joy, asserted visibility and hope for a different future collide with a repressive order nearing exhaustion. Each attempt at excessive control reveals its own absurdity and paradoxically fuels the conquest of new rights. From these nights of monitored celebration emerged forms of mobilisation, solidarity and public recognition that profoundly transformed the legal and social landscape. New Year’s Eve, far from being only a moment of vulnerability, thus appears as a powerful engine of progress, where celebration becomes a political force and an excess of life ultimately opens the way to equality. It remains only to raise our glass, champagne or not, to those New Year’s nights when celebration became an act of emancipation.

Curiosity Piqued?

1. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

2. Steve Charters, Champagne: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the Iconic Region, London, Mitchell Beazley.

3. Philippe Perrot, Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century, New Haven, Yale University Press.

4. William A. Peniston, Pederasts and Others: Urban Culture and Sexual Identity in Nineteenth-Century Paris, New York, Harrington Park Press, 2004.

5. Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

6. Maurice Agulhon, The Republican Circle: Bourgeois Sociability in France, 1810–1848, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

7. Florence Tamagne, A History of Homosexuality in Europe, New York, Algora Publishing.

8. William C. Carter, Proust in Love, New Haven, Yale University Press.

9. Régis Revenin, Homosexuality and Male Prostitution in Paris, 1870–1918, Paris, L’Harmattan.

10. Rod Phillips, A Short History of Wine, London, Penguin.

11. Roger Shattuck, Proust’s Way, New York, W. W. Norton.

12. Leo Bersani, Homosexuality and Proust, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

13. George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940, New York, Basic Books.

14. Le Chat Noir, historical sources and exhibition catalogues, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica.

15. Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, New York, Knopf.

16. Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present, New York, William Morrow.

17. John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

18. Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons, Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians, New York, Basic Books.

19. Susan Stryker and Jim Van Buskirk, Gay by the Bay: A History of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, San Francisco, Chronicle Books.

20. Martin Duberman, Stonewall, New York, Plume.