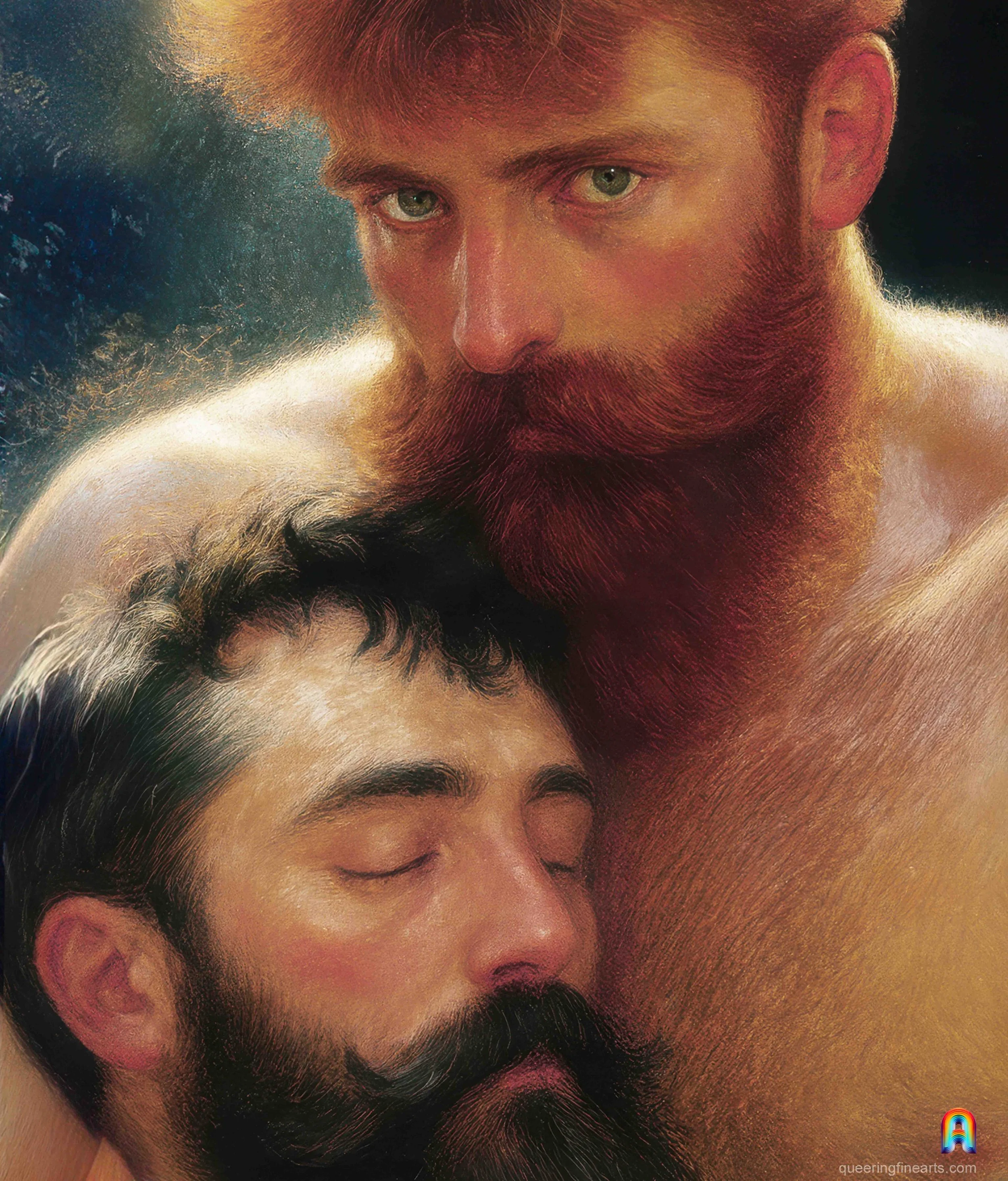

The Radiant Instant

Attributed to the circle of Solomon J Solomon (1860–1927)

Oil on canvas, c. 1895

Private collection

The Radiant Instant

(Garden of M…, August 1895)

The sun bites the nape, weighs down the shoulders,

And in the motionless air where the light trembles,

Slow-moving men speak, their mouths full of fever

And of a desire that never quite finds words.

They are languid, all of them, and the sweat that slips

Carves a trail of salt on skins burning for more;

They say “love” with mouths that glow like embers,

As split earth waits for the sudden storm.

Their hands gather, at the edge of drying pools,

Overripe fruit, swollen with bursting juices;

Their laughter runs deep, their voices resounding,

Rolling through the furnace, singing now and then.

One of them, eyes closed, feels a bitter orange

Whose rind has kept the shape of his clenched fist;

Another, loosening his light summer shirt,

Lets the sun glide far lower than his waist.

They speak of kisses, embraces, tendernesses,

With heavy words, laden with honey and joy,

And the heat stirs, in the hollow of their youth,

The fierce taste of living without fear.

The whole garden is nothing but a trembling body

Under the rough caress and blaze of the sun;

And each man, standing, burning, breathing, seems

To call for the coolness that comes before sleep.

To M…, in the furnace of his garden.

— An Unknown.

Secret Garden

Although the work is attributed to the circle of Solomon J. Solomon (1860–1927), it is worth recalling that the London-born painter, celebrated for his highly finished male nudes and the luminous sensuality of his historical scenes, spent a formative period in Paris studying with Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Paul Laurens, leading masters of grand academic painting. Their rigorous discipline shaped his taste for precise anatomy, sculptural modelling, and radiant flesh tones.

Modern scholarship has rightly dwelled on the emotional and erotic charge of Solomon's work. His male figures, rendered with a distinctive tenderness, and the affectionate nature of some personal relationships have led historians to interpret his work through the lens of a discreet homosexual sensibility, a reading that aligns with the social constraints surrounding same-sex desire in Victorian England. The sensuality of his male subjects and the coded atmosphere of certain compositions strongly reinforce this interpretation.

Solomon's Parisian stay was only one chapter of a broader artistic path. His mature style, developed back in Britain, combined academic naturalism with a fin-de-siècle fascination for sunlit flesh, plein-air settings, and heightened emotional intimacy—a combination that anchors this painting within the artistic climate of the 1890s.

To fully understand the broader resonances of this period, it is natural to look toward France, which remained a central engine of artistic innovation. A more nuanced mapping of male desire and intimacy in French art of the time emerges not from speculation but from formal analysis. Frédéric Bazille's canvases, filled with male bodies bathed in light, are now studied for their intimate and homoerotic charge. Gustave Caillebotte's recurring male models, captured in private moments, and Toulouse-Lautrec's depictions of ambiguous and languid figures sketch a subtle cartography of desires that dared not speak their name.

This artistic undercurrent was mirrored in literature. Verlaine and Rimbaud embodied its most blazing form, mixing passion and ruin. Gide would later write openly about what others concealed, while Proust, through his portraits of men, gave voice to the nostalgia of a hidden world. Together, these creators reveal a constellation of homosexual impulses that, despite suffocating social codes, found in art a crucial space for expression where desire could burn in the open.

Curiosity Piqued?

Painters

Frédéric Bazille (1841–1870) occupies a singular place in the early history of Impressionism. Art historians have noted his frequent depictions of the male nude, often imbued with a discreet yet palpable sensuality. In Bazille: Classical Impressionist (Musée Fabre, 2023), curator Michelle Haddad observes that works such as Young Man Nude Lying on the Grass and La Toilette "present an innovative sensuality that challenges the conventional codes for representing the male body." His profound friendships with Monet and Renoir, whom he painted in works like Réunion d'atelier (The Artist's Studio), suggest an intense homo-social dimension that offers a fresh perspective on his oeuvre.

Edgar Degas (1834–1917) presents a different case. While recent scholarship, including the exhibition Degas and the Nude (Musée d'Orsay, 2012), acknowledges his close and sometimes intense male friendships—notably with the writer Ludovic Halévy—no evidence suggests these relationships were physically consummated. His artistic focus remained predominantly on the female figure. Nevertheless, the emotional texture of these friendships complicates the boundaries between platonic affection, intellectual admiration, and latent desire.

Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894) offers far less ambiguity. His biographer Kirk Varnedoe, in Gustave Caillebotte: A Retrospective (2000), analyses paintings like Man at His Bath as constituting a "radical break with convention, suggesting an intimate gaze upon masculinity." This interpretation was profoundly reinforced by the Metropolitan Museum's 2018 acquisition of a part of Caillebotte's personal collection of male erotic photographs, casting decisive light on the painter's private interests and the underpinnings of his artistic gaze.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) immersed himself in a world of fluid identities and overt sensuality. As explored in Toulouse-Lautrec and Eroticism (RMN, 2021), his drawings for the Ellesseries and his portraits of figures like the clown Cha-U-Kao document a fluid and non-judgmental vision of sexuality, mapping the desires that flourished in the margins of Parisian nightlife.

Writers

Paul Verlaine (1844–1896) and Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) remain the most flamboyantly emblematic pair of their era, their relationship—a turbulent mix of intense passion and destructive chaos—openly documented in police records from Brussels (1873) and their own correspondence. As Jean-Luc Steinmetz notes in his biography Rimbaud (Fayard, 2021), their "life together was marked by passion and violence," creating one of the most incandescent and consequential chapters in French literary history.

André Gide (1869–1951) moved from implication to explicit statement. With the deliberate publication of Corydon (1924) and his autobiography If It Die... (1926), he shattered the prevailing silence surrounding homosexual love. As Frank Lestringnant demonstrates in André Gide l'inquiéteur (Flammarion, 2012), Gide transformed private confession into a public and political act, challenging the social codes of his time.

Marcel Proust (1871–1922) undertook the most extensive literary exploration of male homosexuality of his age. Sodom and Gomorrah (1921-1922) meticulously dissects the secret lives, social hypocrisies, and intricate codes governing men who love men, most memorably through the tragic figure of Baron de Charlus. In his definitive biography Marcel Proust (Gallimard, 1996), Jean-Yves Tadié illustrates how the author transmuted his own experience and observations into a vast, nuanced cartography of hidden desire.

Together, these painters and writers reveal a constellation of homosexual expressions — acknowledged, veiled, or sublimated — that ran through the Belle Époque. Recent historiography, notably the collective volume Homosexualités dans le monde artistique (CNRS Éditions, 2018), shows how these trajectories form a discreet yet decisive network: that of artists who found in creation a space to say what the world refused to hear.

L'Instant Radieux

(Jardin de M..., août 1895)

Le soleil mord la nuque, accable les épaules,

Et dans l'air immobile où danse la lumière,

Des hommes, lents, parlent, la bouche pleine de fièvre

Et de désir qui ne se formule pas.

Ils sont tout alanguis, et la sueur qui coule

Creuse un sillon de sel sur les peaux qui ont soif ;

Ils disent "amour" avec des bouches qui brûlent

Comme la terre fendue attend l'orage bref.

Leurs mains cueillent, au bord des bassins qui s'évaporent,

Des fruits trop mûrs, gonflés de leurs sucs éclatants ;

Leurs rires sont profonds, leurs paroles sonores

Roulent dans la fournaise, et chantent, par instants.

L'un d'eux, les yeux fermés, sent une orange amère

Dont l'écorce a gardé la forme de son poing ;

Un autre, dénouant sa chemise légère,

Laisse le jour glisser bien plus bas que ses reins..

Ils parlent de baisers, d'étreintes, de tendresses,

Avec des mots pesants, lourds de miel et de joie,

Et la chaleur exalte au creux de leurs jeunesses

Le goût violent de vivre, et d'être sans effroi.

Le jardin tout entier n'est qu'un grand corps qui tremble

Sous la caresse rude et l'éclat du soleil ;

Et chaque homme, debout, brûle, respire et semble

Appeler la fraîcheur précédant le sommeil.

À M... dans la fournaise de son jardin.

— Un Inconnu.