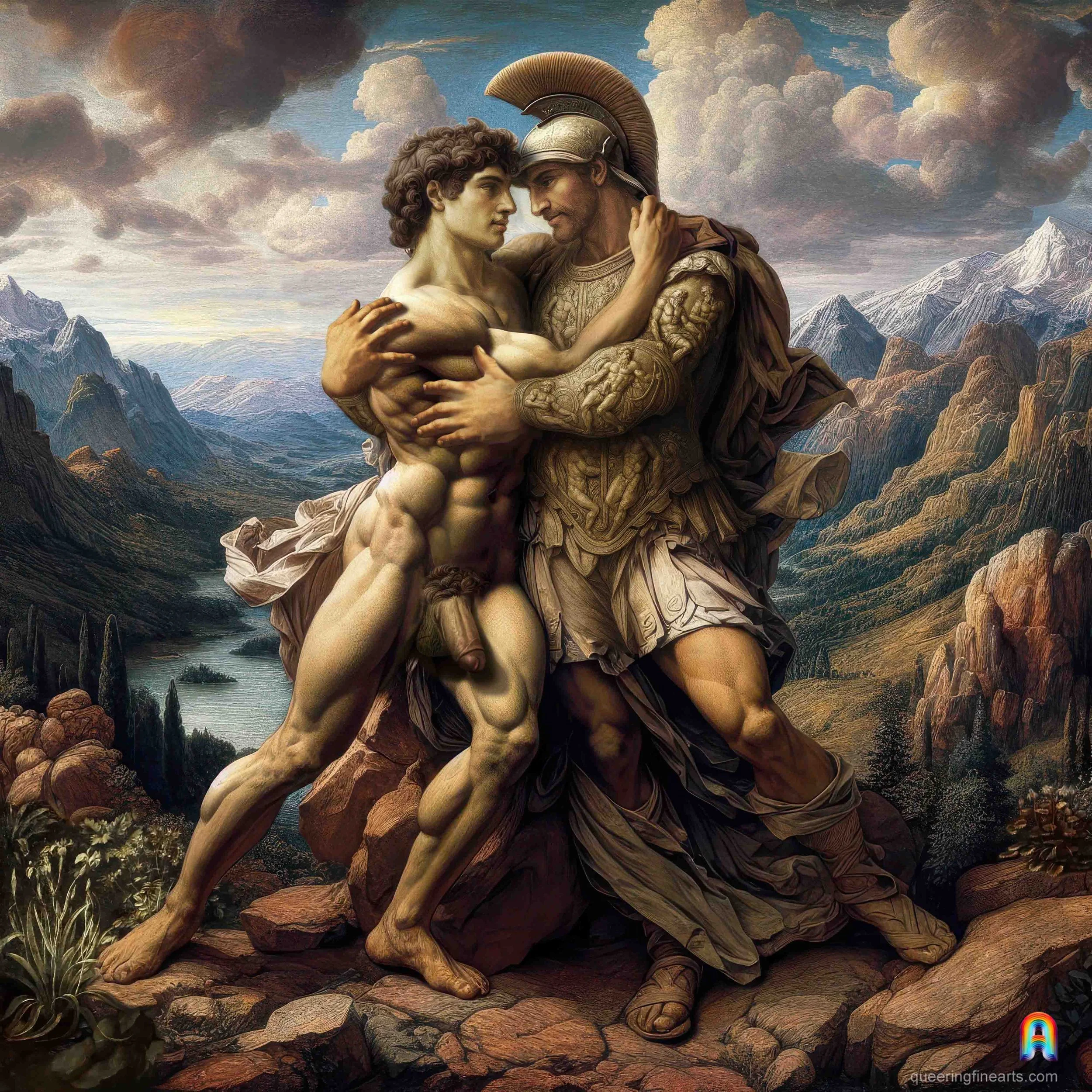

Sacred Band of Thebes, Epaminondas and Cephisodorus

Italian School

Tempera and oil on panel, circa 1540–1550

Private collection

Lovers in Arms

This painting, recently reappeared in a private collection, fascinates as much by its subject as by its uncertain attribution. It shows Epaminondas, the great Theban strategist, armored and helmeted, embracing Cephisodorus, his companion-in-arms and lover, depicted in the fullness of his youth and his nudity. Their bodies, powerful and vibrant, meet in a gesture both heroic and intimate, an interlacing where military glory and carnal tenderness, iron and flesh, action and love converge. The dramatic landscape surrounding them—dark mountains, stormy sky—amplifies the tragic and sensual dimension of the scene.

Philosopher and Warrior

Epaminondas (c. 418–362 BC) is one of the greatest military leaders of ancient Greece. As strategist of Thebes, he broke Spartan power at the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC), overturning the balance of the Greek world. Philosopher as well as general, trained in music and Pythagorean thought, he embodied an ideal of complete humanity. Cephisodorus, younger, was not only his disciple but also his lover: ancient sources explicitly mention their relationship, inscribing it in the Theban tradition of sacred couples. Together, they represented the perfect fusion of military courage and amorous fidelity.

Bound by Eros and Death

At the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC), Epaminondas was mortally wounded and Cephisodorus fell at his side, their union sealed in death as in life. Plutarch describes Epaminondas as “a man whose temperance was equal to his bravery, and who never knew a bond more noble than that of amorous friendship”¹. Pausanias reports that Thebes honored the memory of these companions with the same respect it accorded to the Sacred Band². Their shared fate made them a model of warrior eros, comparable to the Sacred Band of Thebes that Plutarch praises with admiration: “An army composed of lovers is unconquerable, for none would ever flee the idea of appearing cowardly in the eyes of his beloved.”³

Between Michelangelo and Leonardo

The attribution of the work remains at the center of debate. The anatomical vigor, the monumentality of the postures, and the sculptural modeling of the torsos undeniably evoke Michelangelo: the taut muscles recall the ignudi of the Sistine ceiling or the figures of the Last Judgment. Yet other elements suggest the hand of Leonardo da Vinci: the melancholy softness of Cephisodorus’s face, the sfumato that blurs contours and dissolves flesh into vaporous light, the atmospheric depth of the landscape that envelops the scene in intimate poetry. Where Michelangelo privileges heroic monumentality, Leonardo allows interiority and psychological nuance to emerge.

The Crossroads of Desire

Rather than a definitive attribution, the painting seems to stand at the crossroads of the two great languages of the Renaissance: the muscular drama of Michelangelo and the luminous subtlety of Leonardo. This ambiguity feeds its mysterious aura: is it the heroic cry of an aging Michelangelo or the veiled confession of a Leonardo in love with inner harmonies? In any case, Epaminondas and Cephisodorus appears as an aesthetic and symbolic threshold, where the eternity of Greek history meets the eternity of human desire.

Curiosity Piqued?

Plutarch, Life of Pelopidas, XVII: « …ἡ σωφροσύνη δὲ ἡ τοῦ Ἐπαμινώνδου τῇ ἀνδρείᾳ ἴσην ἐποιοῦσα, καὶ τὸ μὴ δεσμὸν ἄλλον ἢ τὸν ἐρωτικὸν τῆς φιλίας ἔχειν… » (“The temperance of Epaminondas equaled his bravery, and he never knew a bond more noble than that of amorous friendship.”)

Pausanias, Description of Greece, IX, 15, 3: mention of the memory of the Theban companions honored equally to that of the Sacred Band.

Plutarch, Banquet of the Seven Sages, 18: « ὁ ἐκ τοῦ ἔρωτος σύνταξις στρατιωτῶν ἄμαχος καὶἀνίκητος… » (“An army composed of lovers is unconquerable, for none would ever flee the idea of appearing cowardly in the eyes of his beloved.”)