The Old Master Workshop with Model

In the manner of the late Renaissance, which might have been painted c. 1600–1620

Where Chiaroscuro Meets Passion

This composition evokes the workshop of an old master, where the painter engages in dialogue with his nude model amidst fragments of artistic memory: antique statues, Greek vases and paintings from across the ages. Balanced between chiaroscuro and erudition, the image spans centuries to recompose a universe where male gazes encounter and respond to one another.

Reclaiming the Masters

The work presents itself as an ode to masculinity and homosexuality in the art of the past , an aspect too often obscured but here triumphantly reclaimed with pride. It blurs the solemnity of academic tradition by inserting an element of mischievous play, reminding us that the history of art can also be a field of delight and invention.

The Painter’s Mirror

It is known that the creator of Queering Fine Arts has inscribed his own likeness here, lending his features to the painter. In this imagined museum, Renaissance humanism meets contemporary queer freedom: the classical masters rediscover a new complicity and the workshop becomes a space of memory and reinvention, where desire, heritage and cultural affirmation are intertwined.

After the Posing

And after the sessions of posing, what then? Some contemporaries whispered that master and model abandoned themselves to passionate embraces upon the draperies carelessly cast to the floor. Hands wandered over bodies as brushes caressed canvas; sweat replaced the warm paste of paint; rods of manhood took on the hardness of bronze; and the languor of the workshop became the stage of a fusion where art and flesh dissolved into one.

Would you be able to identify all the Easter Eggs hidden in the painting, elements that pay tribute to the masculinity and homosexuality in art?

There’s more than just a touch of ‘classic’ male beauty to uncover!

Roman Vase with Phallic Decoration

Colchester (Camulodunum), Roman province of Britannia, 1st–2nd century CE

Local barbotine ware (Colchester ware)

Colchester Castle Museum

This vase, produced in the ceramic workshops of Colchester, is adorned with phalluses applied in relief. Such representations, common in Roman art, were less about eroticism than about an apotropaic function: the phallus, or fascinum, was a symbol of protection against the evil eye and a bearer of fertility, health, and prosperity.

The use of phallic motifs on everyday objects such as lamps, amulets, or drinking vessels reflects the permeability between domestic, religious, and popular spheres in Roman culture. The repetitive and humorous nature of this decoration also suggests a playful dimension, typical of the Colchester workshops, well known for their richly decorated barbotine beakers.

In a society where male eroticism could be expressed in varied contexts, this type of phallic décor could also be perceived as an allusion to virile power shared between men. Roman sexual imagination gave a visible place to homoerotic relations, often associated with vigor and masculinity, which lends this vase an expanded reading: at once protective talisman, object of humor, and possible celebration of male desire.

Double Portrait, known as Raphael and a Friend

Attributed to Raphael (1483–1520)

Oil on canvas, c. 1518–1519

Musée du Louvre, Paris

This enigmatic double portrait shows, on the left, the figure traditionally identified as Raphael, alongside a bearded companion whose identity remains uncertain. The assured hand resting on the shoulder and the exchange of glances suggest a singular closeness, imbued with confidence and intimacy.

The work has given rise to much debate regarding the identity of the figure on the right: a close friend, a patron, or perhaps the pupil Giulio Romano. Yet the composition, which grants unusual prominence to an affectionate gesture between two men, has also been read as the expression of a bond surpassing mere camaraderie. In the cultural climate of the Renaissance, where the legacy of Antiquity celebrated idealized male friendships, this dimension opens the way to a sensitive, even homoerotic, interpretation of the painting.

Some art historians, drawing on biographical hints and the intimate tone of certain works, have advanced the hypothesis of Raphael’s homosexuality, long silenced in traditional criticism. This portrait may thus reflect not only the spirit of Renaissance humanism, but also a more personal reading, in which the artist hints at his own attraction and affections through the image of the male body and the staging of bonds between men.

Acquired by the Louvre in the 19th century, this canvas remains one of the few supposed likenesses of the painter and a striking example of humanist portraiture, where art explores the nuances of desire, affection, and male complicity.

The Vitruvian Man

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

Ink and wash on paper, c. 1490

Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

This drawing, one of the most famous of the Renaissance, illustrates the ideal proportions of the human body as described by the Roman architect Vitruvius: the man inscribed in a circle and a square embodies the harmony between microcosm and macrocosm, between body and universe. Leonardo combines scientific observation with aesthetic pursuit, translating into image the humanist ideal of a rational and universal body.

Beyond its theoretical function, the work also reveals Leonardo’s passionate attention to the male body, which he studied with a gaze at once scientific and sensitive. His numerous anatomical drawings and notebooks disclose a particular fascination for virile beauty. Contemporary testimonies, sometimes critical, recall his attraction to young men and his homosexuality, lived in a society where it remained half-clandestine.

Thus, The Vitruvian Man can be read not only as a manifesto of Renaissance science, but also as the intimate affirmation of a desire: to raise the male body to the rank of the ideal measure of all things.

Torso of Meleager

Roman copy after Polyclitus (Greek original circa 440 BCE)

Marble, height approx. 1.50 m

Pio-Clementino Museum, Vatican Museums, Rome, Italy (similar examples preserved in the Louvre, Naples, and various European museums)

This statue of Meleager, a Greek mythological hero, is a Roman copy of an original by Polyclitus. The torso illustrates the ideal of masculine beauty in antiquity, with perfect proportions and harmonious musculature, characteristic of the classical style. Meleager, a young hero whose exploits were celebrated, embodies not only virility but also the idealization of emotional bonds between men in Greek culture.

The relationship between Meleager and his companions in the Calydonian boar hunt could be interpreted as expressions of shared intimacy and desire. In a world where relationships between young men and adults were often valued, as evidenced by the practices of ephebes or athletes in the palaces and gymnasiums, intimate friendships sometimes served as a space for erotic exploration. These bonds, often based on education and physical camaraderie, were also seen in Dionysian cults, where initiatory rituals included emotional and sensual relationships among participants.

This sculpture reflects how both Greek and Roman antiquity celebrated beauty, virility, and male eroticism, while also allowing for the portrayal of homoerotic relationships in social and artistic contexts, recognizing them as a natural component of social life and the visual culture of the time.

Attic Red-Figure Cup: Zeus and Ganymede

Attributed to the Berlin Painter (c. 500–490 BCE)

Attic red-figure ceramic

Archaeological Museum (similar examples in the Louvre, Berlin, and several European collections)

This cup illustrates one of the most explicit tales of Greek homoeroticism: the abduction of Ganymede, the young Trojan prince, by Zeus. The bearded god, crowned with laurel, draws toward him the handsome youth, shown nude, with curly hair and adorned with the attributes a young man in his prime.

In mythology, Ganymede became Zeus’s divine lover and cupbearer on Olympus. This scene consecrated in the Greek imagination the legitimacy of initiatory relationships, that is, the erotic and educational bond between an adult and a younger man, considered at the time to be a noble and formative form of love.

The use of such cups in the context of the symposion (male banquet) reinforced this dimension: they staged and celebrated attraction to male beauty while offering the guests images that legitimized and exalted homoerotic bonds.

Double Bronze Dildo

China, Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

Cast and polished bronze

Henan Museum, China

This exceptional object, shaped as a double phallus, testifies to the existence of sophisticated erotic accessories in ancient China. Made of solid bronze, it could be used alone or by two partners, revealing a dimension of sexuality that was both intimate and social.

While it may have served in heterosexual contexts, its double form strongly suggests use between same-sex partners, opening the way to an explicitly homosexual interpretation. In a society where male–male relations were known, and at times even valued among certain elites—this object illustrates a concrete practice of desire between men, far beyond imagination or myth.

Through its phallic realism and material power, this double dildo reminds us that the history of human sexuality, far from uniform, was also shaped by acknowledged homoerotic practices, of which this rare bronze offers a tangible testimony.

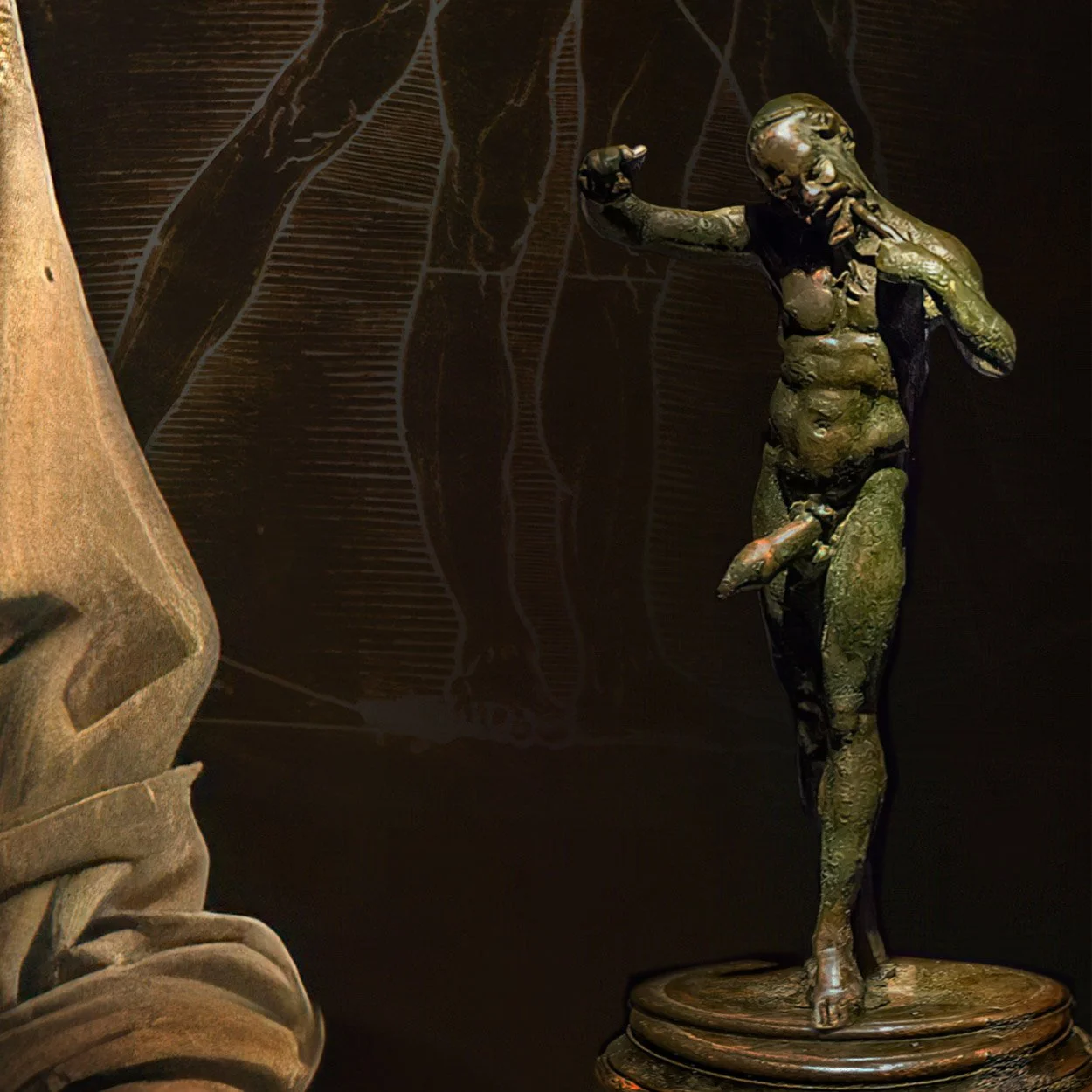

Statuette of Priapus

Roman Art, 1st–2nd century CE

Bronze

Archaeological Museum (provenance varies by collection, similar examples in Pompeii, Naples, and various European museums)

This small bronze statuette of Priapus highlights the Greco-Roman god of fertility, gardens, and carnal pleasures, depicted with an oversized phallus. Although traditionally associated with agricultural prosperity, the image of Priapus went beyond the concept of heterosexual fertility to include the expression of shared male sexuality.

In the context of Roman antiquity, where relationships between men were integrated into sexual and social culture, Priapus's phallus symbolized not only fertility related to nature and women but also sensuality and pleasure between men. Ancient frescoes and vases show Priapus in clearly homoerotic scenes, emphasizing the diversity of meanings in Roman imagination.

This statuette illustrates a world where male eroticism was recognized, often integrated with masculinity, but also celebrated as a sign of complicity and enjoyment between men. In antiquity, the boundary between the sacred, the profane, and homoeroticism was often blurred, allowing Priapus to represent a plurality of male desires and a sacred dimension of eroticism.

Apollo and Hyacinthus (detail)

Nicolas-René Jollain (1732–1804)

Oil on canvas, 1769

Louvre Museum, on loan to the Domaine de Versailles, Petit Trianon

This painting depicts the god Apollo mourning the death of Hyacinthus, the beautiful youth he loved passionately. According to Greek mythology, Hyacinthus was struck fatally by a discus thrown during a game, an accident said to have been provoked by the jealousy of Zephyrus. From his blood sprang the flower that bears his name.

Jollain conveys Apollo’s emotion with intensity, his hand pressed to his forehead, while the lifeless body of the young man rests on his knees. The red drapery, the flowers, and the lyre recall the god of music and the arts, but also the erotic charge of the ancient tale.

This myth is one of the clearest testimonies of divine homosexuality in Greek culture, where love between men could be exalted by art and poetry. In the eighteenth century, its representation offered painters the opportunity to stage the sensuality of male bodies and to evoke, under the guise of mythology—the tragic beauty of homosexual desire.

Bronze Hydria: Dionysos and Silenus

Northern Greece, second half of the 4th century BCE

Hammered and cast bronze

Archaeological Museum (provenance and similar examples preserved in Athens and various European museums)

This bronze hydria, used for serving water or wine, is adorned with a relief depicting Dionysos, god of wine and ecstasy, supported by an elderly Silenus. The scene embodies both the initiatory dependence of the young god on his mentor and the ambivalence between youth and old age in the Dionysian sphere.

In Greek culture, Dionysos was often associated with forms of sexual transgression, blurring of gender roles, and homoerotic desire. Here, the bodily intimacy between the adolescent god and the bearded Silenus, a figure of intoxication and carnal knowledge, clearly evokes the pederastic relationships that were part of Greek social fabric.

This object illustrates how Dionysian iconography was used to legitimize and magnify homosexual bonds: wine, the banquet, and the cult of Dionysos provided a ritual space where pleasure, initiation, and male eroticism intersected.

Cameo Depicting Antinous

Roman Empire, 2nd century CE

Carved agate, later gold setting

Museum (similar examples preserved in the Louvre, the British Museum, and various European collections)

This agate cameo depicts Antinous, a young Greek from Bithynia and lover of Emperor Hadrian. Tragically dying in 130 CE during a trip to Egypt, Antinous was immediately deified by the mourning emperor, who erected statues and founded cities in his name. His idealized face, with regular features and wavy hair, became a major iconographic model of male beauty in Roman art.

The story of Antinous illustrates one of the most famous homosexual relationships of antiquity, lived openly by an emperor and celebrated through images disseminated throughout the Empire. The countless effigies that remain testify to a personal love transformed into an official cult, where Hadrian’s intimate desire and memory were given universal value.

Attic Red-Figure Kylix: Homosexual Scene

Athens, 5th century BCE

Attic red-figure ceramic

Archaeological Museum (similar pieces preserved in the Louvre, Berlin, and the British Museum)

This cup illustrates an erotic scene between three men, painted with unrestrained naturalism. Designed to be used at symposia, male banquets blending wine, music, and intimate exchanges, it reflects the place that homoeroticism held in classical Greek society.

Far from being marginal, these representations were part of a codified repertoire, where male attraction was staged as a shared pleasure and a legitimate component of social life. Within the banquet setting, they served both to arouse excitement and to celebrate the beauty and vigor of the male body.

Thus, this vase provides direct testimony to the visibility of male homosexuality in ancient Greek society, perceived not as a transgression, but as one of the many expressions of desire and conviviality.

Attic Red-Figure Kylix: Initiatory Scene

Athens, 5th century BCE

Attic red-figure ceramic

Archaeological Museum (comparable examples in the Louvre, the British Museum, and Berlin)

This drinking cup illustrates a scene of seduction between an adult bearded man and a young man, emblematic of the emotional and erotic bonds in ancient Greek culture. The older man embraces the young man while he holds a cup and a vine branch, symbols of the banquet and the Dionysian world.

In classical Athenian society, relationships between an older man and a younger partner were often seen as a legitimate form of education and the transmission of values. These images, common on vases used at symposia, remind us that male homosexuality was fully integrated into the social and cultural practices of the time.

Thus, this vase stands as a testament to the visibility of love between men in ancient Greece, celebrated as a bond that was both erotic, educational, and civic.

Statuette of Priapus

Greece or Rome, 1st century BCE – 2nd century CE

Molded terracotta

Archaeological Museum (similar examples preserved in Naples, Rome, and Athens)

This figurine of Priapus, easily recognizable by his gigantic phallus, embodies the ambivalent role of the god: protector of harvests, homes, and carnal pleasures. Placed in gardens or inside homes, it served both as an apotropaic talisman to ward off the evil eye and as a symbol of fertility and prosperity.

Beyond this protective function, Priapus was also a symbol of desire and sexuality, particularly homoerotic, in a culture where relationships between men were accepted and celebrated. His representation extended beyond female fertility to include the vigor of shared male desires, illustrating a broader view of eroticism in antiquity.

This statuette is a testament to the seamless integration of religion, popular humor, and sexuality, a blend that characterized the Greco-Roman imagination, where male eroticism was not marginalized but fully embraced and often celebrated in social contexts.